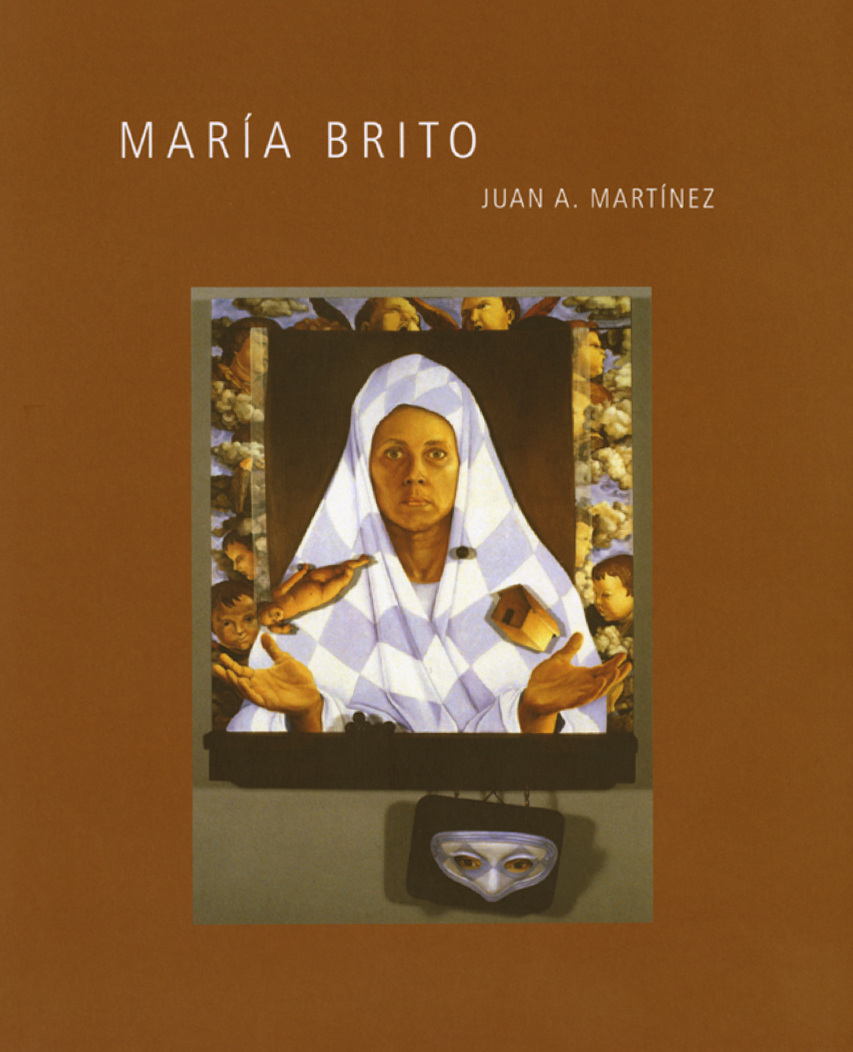

Juan A Martinez, 2012

Maria Brito’s assemblages, mixed-media constructions of mostly found objects and wood, may be differentiated into boxes, interiors, objects, and installations. In all cases their overall technique falls within a practice in the fine arts that dates back to the period of High Modernism in the 1910s as seen in the works of Cubists, Constructivists, and Dadaists. The technique is concisely defined by Diane Waldman in her book on the subject: “While assemblage differs from painting in that it is basically a three-dimensional rather than a two dimensional medium, it is also distinct from conventional sculpture as it is formed in an additive process rather than shaped or carved from a monolith. It also diverges from collage, to which it is otherwise directly related, since it moves away from the plane and actively intrudes on the space of the spectator. ” [i] Brito’s assemblages, or as she like to call them “mixed media sculpture,” fulfill all of these characteristics and they particularly intrude on the space of the spectator. Moreover, assemblage, like collage, not only introduced a new technique for making art, but a wide new range of materials, mostly industrial and of every day use, not traditionally associated with art. This practiced opened Brito’s eyes to the artistic potential of household objects in her neighborhood garbage piles; the same piles that her parents had raided when they first arrived in Miami looking to furnish their apartment. Of the pioneers of assemblage, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Vladimir Tatlin, and Kurt Schwitters, Maria Brito’s have a distant familiarity with those of Schwitters in their sturdy construction and the use of discarded objects.

Closer to home, the magical boxes of Joseph Cornell, the first American master of the medium, had a more direct impact on Maria Brito’s mixed media sculpture. Brito learned of Cornell in college and some of her early boxes have an affinity with his as far as the making of small, poetic, mysterious art out of displaced worn objects. Maria Brito’s, however, are more grounded in personal experiences.

Assemblage took hold in the United States in the late 1950s, and its practice expanded quickly. Already in 1961, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a major and now-historic exhibition entitled The Art of Assemblage. William C. Seitz, its curator, aimed to acknowledge and celebrate the “current wave of assemblage,” which he defined as “a generic concept that would include all forms of composite art and modes of juxtaposition.” [ii] Neo-Dada and Pop artists included in that exhibition raised the medium to new heights in terms of scale and tangibility. Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines,” Louise Nevelson’s cathedrals, Marisol Escobar’s figurative constructions, George Segal’s environments, Lucas Samarra’s objects, and Edward Kienholz’s tableaux are among the most memorable art of the1960s. Maria Brito’s mix-media constructions share strong connections, consciously or not, to those of Nevelson and Keinholz. Brito’s work in wood, like Nevelson’s, has a sturdy, hefty quality to it. Both artists also struggled with the application of paint to found wood. Moreover, both of their constructions speak a symbolic language through elements often borrowed from Christian art and architecture. With Kienholz, Brito shared the desire for building complex, unsettling, and aggressive tableaux.

She works by carefully choosing and (dis)placing discarded household items in stage-like spaces, following an intuitive process:

I do not have a set process for developing an idea into a finished piece. I work by instinct, and the content and subject undergo transformations as I search for the eventual forms and expressions. Ideas for a particular work thus develop intuitively. Rarely does the final outcome resemble the initial or preliminary sketch (which I make of the piece in progress-and not before I start the piece-pretty much as taking a photograph in order to document what is there at that moment in time). As the three-dimensional piece begins to take shape, more complete ideas are dictated by the work itself. I become one with the work and I am able to sense its needs.[iii]

One of the salient qualities of Maria Brito’s mixed media sculture is their emotional and symbolic charge. Chairs, beds, doors, picture frames, mirrors, clocks, suitcases, faucets, jars, masks and old photos exist as such in her work, yet suggest meaning. The symbolic character of Maria Brito’s work has been pointed out by a number of critics. “Brito’s art contains symbols that invite decipherment,” yet “refuse to settle into a single narrative,” wrote Chris Hassold. [iv] Taking a closer look Lynette Bosch observed that Brito’s art “employs a substitutive metonymy that replaces narrative and figure with metaphor and object.” [v] Here Bosch touches on two significant and related aspects of Brito’s mixed media sculpture. One is the primacy of the object over the figure, which it substitutes, and the use of juxtaposition to suggest a layered discourse rather than a linear narrative.

There is a general consensus that Brito’s mixed media constructions of the 1980s and 1990s suggest, memory/dream, rupture/dislocation and/or pain/anger. Such a vision of the self and humanity is inspired in certain experiences, such as leaving her homeland as a child, adapting to a new life in the United States of the 1960s, receiving a Cuban Catholic upbringing in an Anglo-Saxon culture, marriages, motherhood, bouts with sickness, and an honest and relentless search for self-knowledge and realization. Of all of these experiences, the Catholic upbringing seems strongly connected to not only some of the symbols used in the work, but to the very nature of her symbolism. “Catholicism is always involved in physical manifestation of physical conditions, always taking inanimate objects and attributing meaning to them. In a way its compatible with art” [vi] This observation by Eleanor Heartney on the iconographic nature of work by contemporary artists who were raised Catholic, applies well to the art of Maria Brito. At home and in church, she encountered religious illustrations, talismans, sculptures, and liturgical objects with potent meaning and power. Later this view of the potential symbolic meaning of objects was reinforced in art and art history classes. At times she borrows Christian symbols, but more importantly what her iconography shares with that of Catholic art is the “taking of inanimate objects and attributing meaning to them.”

Closer to home, the magical boxes of Joseph Cornell, the first American master of the medium, had a more direct impact on Maria Brito’s mixed media sculpture. Brito learned of Cornell in college and some of her early boxes have an affinity with his as far as the making of small, poetic, mysterious art out of displaced worn objects. Maria Brito’s, however, are more grounded in personal experiences.

Assemblage took hold in the United States in the late 1950s, and its practice expanded quickly. Already in 1961, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a major and now-historic exhibition entitled The Art of Assemblage. William C. Seitz, its curator, aimed to acknowledge and celebrate the “current wave of assemblage,” which he defined as “a generic concept that would include all forms of composite art and modes of juxtaposition.” [ii] Neo-Dada and Pop artists included in that exhibition raised the medium to new heights in terms of scale and tangibility. Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines,” Louise Nevelson’s cathedrals, Marisol Escobar’s figurative constructions, George Segal’s environments, Lucas Samarra’s objects, and Edward Kienholz’s tableaux are among the most memorable art of the1960s. Maria Brito’s mix-media constructions share strong connections, consciously or not, to those of Nevelson and Keinholz. Brito’s work in wood, like Nevelson’s, has a sturdy, hefty quality to it. Both artists also struggled with the application of paint to found wood. Moreover, both of their constructions speak a symbolic language through elements often borrowed from Christian art and architecture. With Kienholz, Brito shared the desire for building complex, unsettling, and aggressive tableaux.

She works by carefully choosing and (dis)placing discarded household items in stage-like spaces, following an intuitive process:

I do not have a set process for developing an idea into a finished piece. I work by instinct, and the content and subject undergo transformations as I search for the eventual forms and expressions. Ideas for a particular work thus develop intuitively. Rarely does the final outcome resemble the initial or preliminary sketch (which I make of the piece in progress-and not before I start the piece-pretty much as taking a photograph in order to document what is there at that moment in time). As the three-dimensional piece begins to take shape, more complete ideas are dictated by the work itself. I become one with the work and I am able to sense its needs.[iii]

One of the salient qualities of Maria Brito’s mixed media sculture is their emotional and symbolic charge. Chairs, beds, doors, picture frames, mirrors, clocks, suitcases, faucets, jars, masks and old photos exist as such in her work, yet suggest meaning. The symbolic character of Maria Brito’s work has been pointed out by a number of critics. “Brito’s art contains symbols that invite decipherment,” yet “refuse to settle into a single narrative,” wrote Chris Hassold. [iv] Taking a closer look Lynette Bosch observed that Brito’s art “employs a substitutive metonymy that replaces narrative and figure with metaphor and object.” [v] Here Bosch touches on two significant and related aspects of Brito’s mixed media sculpture. One is the primacy of the object over the figure, which it substitutes, and the use of juxtaposition to suggest a layered discourse rather than a linear narrative.

There is a general consensus that Brito’s mixed media constructions of the 1980s and 1990s suggest, memory/dream, rupture/dislocation and/or pain/anger. Such a vision of the self and humanity is inspired in certain experiences, such as leaving her homeland as a child, adapting to a new life in the United States of the 1960s, receiving a Cuban Catholic upbringing in an Anglo-Saxon culture, marriages, motherhood, bouts with sickness, and an honest and relentless search for self-knowledge and realization. Of all of these experiences, the Catholic upbringing seems strongly connected to not only some of the symbols used in the work, but to the very nature of her symbolism. “Catholicism is always involved in physical manifestation of physical conditions, always taking inanimate objects and attributing meaning to them. In a way its compatible with art” [vi] This observation by Eleanor Heartney on the iconographic nature of work by contemporary artists who were raised Catholic, applies well to the art of Maria Brito. At home and in church, she encountered religious illustrations, talismans, sculptures, and liturgical objects with potent meaning and power. Later this view of the potential symbolic meaning of objects was reinforced in art and art history classes. At times she borrows Christian symbols, but more importantly what her iconography shares with that of Catholic art is the “taking of inanimate objects and attributing meaning to them.”

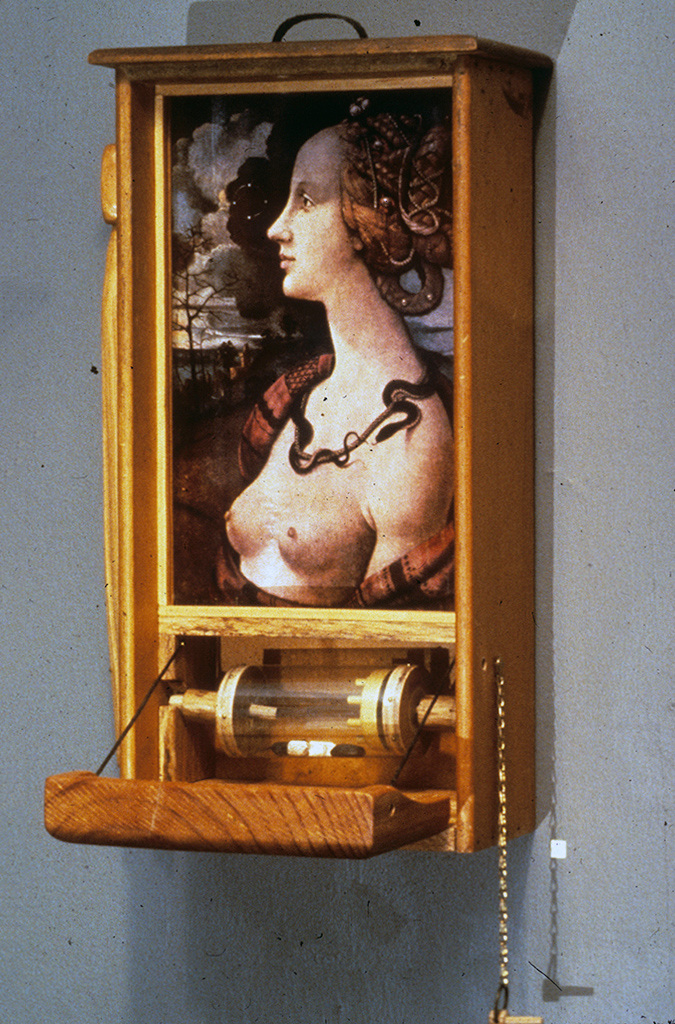

Among Maria Brito’s earlier assemblages, dating to the early 1980s, are small boxes containing objects and reproductions of Western art. Their format is similar to Joseph Cornell’s boxes, which Brito appropriated to her own ends. By comparison her boxes show more elaborate and layered compositions and a rough edge. Brito’s boxes usually consist of weathered found wood divided into two or more compartments, which are filled with objects and images that recur in her work: doors, masks, mirrors, cups, cranks, which in the boxes are miniaturized, as well as images of the sky, violent biblical scenes by Old Masters, and in one, the “Vitruvius man” by Leonardo Da Vinci. The things in these boxes and their juxtaposition suggest symbolic, if enigmatic meaning. Outstanding among her boxes are Epiphany1980, In Lieu of Fragmentation 1980, Memories of the Future 1981,On The Folly of Cleo et all 1981, Restricted Passport 1982, Self-Portrait in Gray and White 1982, and The Room Upstairs 1984.

One of her earliest boxes, Epiphany, is made of an old, small crate that was used to contain ammunitions. The two outstanding elements inside the crate-box are an image of a crucifixion and a cup made of cheesecloth. About the combination of an ammunition crate and the crucifixion, Brito wrote:

Like many Catholics, I am disturbed by the thought that so many abuses have been committed throughout history in the name of the Faith; in the name of God. This, unfortunately, still goes on at many levels and is true, I think, of most religions. The incorporation of a religious image in the context of this particular box comments on the irony of the whole thing. The lower circular opening in front of the crucifixion has metal bronze spikes all around its circumference. They, I feel, add to the idea of pain that is being inflicted not only upon the suffering Christ but also upon the victims of His misinterpreted teachings. [vii]

This identification with Catholicism, but from a critical point of view is an important theme in Brito’s work. Her comments on the cup on the lower compartment share an ironic viewpoint subtly connected to the main theme of the piece. “The cup represents the self. It is also a receptacle. But this latter notion is denied by the fact that the cup is actually made of cheesecloth.” [viii]

A more elaborate box with a rather comprehensive iconography related to personal identity is Self Portrait in Grey and White. Brito’s extensive description and analysis of this piece is worth quoting at length to glimpse her thought process at work:

The piece is an “all-inclusive” self-portrait in that it is a metaphorical representation of the different facets of myself at the time. It has two sides, one “public” and the other one reveals what’s beneath the “surface,” an “interior” of sorts. This explores the idea of duality, which I used in subsequent works. The overall format of the piece is that of a stereotypical house image. The “public” side has a non-functional doorknob on a surface made of wood slats. This serves to make this side of the piece look like a locked door. The only reference to the imagery on the other side of the piece is simple cloud shapes, which can be seen through a rectangular area enclosed by clear plexi at the top end of the structure. The clouds, on this side of the piece, are painted gray.

The “private” side of the piece is divided into five compartments.

The concept came from reading the writings of Carl Jung and his followers, whose philosophy influenced some of my early pieces. Jung uses the “house” as a metaphor for the individual. For example, basements, according to him, represent that which is common to every individual and therefore unites humankind. (Posiblemente sea por eso, porque aqui en Miami no tenemos “basements,” es que estamos tan desiquilibrados !!) The higher one goes in that house-metaphor, the more the individual self is reflected.

Inside the compartment at the bottom, which is enclosed by -or “protected with”-a piece of clear plexi, are images that represent my four children (four, at the time). Their shapes are also stereotypical in keeping with the overall format of the piece. They are cut outs, behind which is a color drawing of a smiling child rendered in a child-like manner. The particular placement of my children at this lower end of the overall structure – which corresponds with a “basement” according to Jungian theory- relates to motherhood, an archetypal concept, and my being part of a larger whole in that sense.

The larger compartment is in the middle of the overall format. Appropriately, I think, it has a prominent red heart. On both sides of the heart are revolving, vertical wood slats with child-like cutouts of figures on both sides of each slat. These represent the parents (Luis and me). Since each parent has both a good and a bad side (yin and yang) each slat has a white and a black figure on each side.

The top compartment represents my studio, my private space, where vestiges of my family life are represented by the faint presence of the two parents (above). This space has a ladder, which reaches toward the uppermost space filled with clouds. This ethereal area alludes to the non-physical space that the (my) mind enters during the act of creation. [ix]

In her earliest self-portrait, a subject that she later and fully developed in painting, Brito explored the issue of identity from a familial/artist and gendered point of view—Maria the mother, Maria the wife, and Maria the artist in her home studio. It should also be noticed that Brito approached the expression of a complex self with certain psychological-metaphysical underpinnings, informed in this case by the theories of Jung and his followers. In the painted self-portraits, often Catholicism provides the means to structure a self-identity, as Jung theories do in this piece.

One of the most plain, yet haunting boxes by Maria Brito is The Room Upstairs: Self Portrait with Two Friends in the collection of the Lowe Art Museum in Coral Gables, Florida. Barely 15 1/2 x 11 1/4 inches, this box is divided into two unequal compartments. The lower section shows a partial domestic interior suggested by a white door set in the middle of a two-toned blue wall and preceded by checkered floor. The smaller upper compartment, more of an attic than a second floor, houses three black and white images of young girls, one split down the middle, and a partly hidden butterfly.

The piece touches on a number of Brito’s themes of the 1980s: domestic interiors, childhood memories, and fragmented self. The theme of childhood memories was inspired in part by interaction with her children, which brought back memories of her own childhood. Not surprisingly these real/fictional memories are often presented in the context of domesticity. In this piece, the sense of memory is evoked by the emptiness of the domestic interior, the fact that although I have described the lower part as an interior, it could also be seen as an exterior, the combination of color and black and white images, and the incongruous butterfly. The content of the memory offers a discourse on the self, made all the more poignant by the split in the self-portrait and the knowledge that the friends are imaginary. The elements of desire, imagination, and fragmentation give the memory a bittersweet taste and posit an expansive view of self. The enlarged and out of place butterfly, which to Brito symbolizes frailty and freedom, offers a happy note to the composition.

Wanting to expand into real space Maria Brito early on began to work on human scale mixed media sculptures. The use of found objects, her vocabulary of forms, and the content of her larger pieces is similar to that of the boxes, except that the theme of domestic interiors became more prevalent in the tableaux.

One of her earliest boxes, Epiphany, is made of an old, small crate that was used to contain ammunitions. The two outstanding elements inside the crate-box are an image of a crucifixion and a cup made of cheesecloth. About the combination of an ammunition crate and the crucifixion, Brito wrote:

Like many Catholics, I am disturbed by the thought that so many abuses have been committed throughout history in the name of the Faith; in the name of God. This, unfortunately, still goes on at many levels and is true, I think, of most religions. The incorporation of a religious image in the context of this particular box comments on the irony of the whole thing. The lower circular opening in front of the crucifixion has metal bronze spikes all around its circumference. They, I feel, add to the idea of pain that is being inflicted not only upon the suffering Christ but also upon the victims of His misinterpreted teachings. [vii]

This identification with Catholicism, but from a critical point of view is an important theme in Brito’s work. Her comments on the cup on the lower compartment share an ironic viewpoint subtly connected to the main theme of the piece. “The cup represents the self. It is also a receptacle. But this latter notion is denied by the fact that the cup is actually made of cheesecloth.” [viii]

A more elaborate box with a rather comprehensive iconography related to personal identity is Self Portrait in Grey and White. Brito’s extensive description and analysis of this piece is worth quoting at length to glimpse her thought process at work:

The piece is an “all-inclusive” self-portrait in that it is a metaphorical representation of the different facets of myself at the time. It has two sides, one “public” and the other one reveals what’s beneath the “surface,” an “interior” of sorts. This explores the idea of duality, which I used in subsequent works. The overall format of the piece is that of a stereotypical house image. The “public” side has a non-functional doorknob on a surface made of wood slats. This serves to make this side of the piece look like a locked door. The only reference to the imagery on the other side of the piece is simple cloud shapes, which can be seen through a rectangular area enclosed by clear plexi at the top end of the structure. The clouds, on this side of the piece, are painted gray.

The “private” side of the piece is divided into five compartments.

The concept came from reading the writings of Carl Jung and his followers, whose philosophy influenced some of my early pieces. Jung uses the “house” as a metaphor for the individual. For example, basements, according to him, represent that which is common to every individual and therefore unites humankind. (Posiblemente sea por eso, porque aqui en Miami no tenemos “basements,” es que estamos tan desiquilibrados !!) The higher one goes in that house-metaphor, the more the individual self is reflected.

Inside the compartment at the bottom, which is enclosed by -or “protected with”-a piece of clear plexi, are images that represent my four children (four, at the time). Their shapes are also stereotypical in keeping with the overall format of the piece. They are cut outs, behind which is a color drawing of a smiling child rendered in a child-like manner. The particular placement of my children at this lower end of the overall structure – which corresponds with a “basement” according to Jungian theory- relates to motherhood, an archetypal concept, and my being part of a larger whole in that sense.

The larger compartment is in the middle of the overall format. Appropriately, I think, it has a prominent red heart. On both sides of the heart are revolving, vertical wood slats with child-like cutouts of figures on both sides of each slat. These represent the parents (Luis and me). Since each parent has both a good and a bad side (yin and yang) each slat has a white and a black figure on each side.

The top compartment represents my studio, my private space, where vestiges of my family life are represented by the faint presence of the two parents (above). This space has a ladder, which reaches toward the uppermost space filled with clouds. This ethereal area alludes to the non-physical space that the (my) mind enters during the act of creation. [ix]

In her earliest self-portrait, a subject that she later and fully developed in painting, Brito explored the issue of identity from a familial/artist and gendered point of view—Maria the mother, Maria the wife, and Maria the artist in her home studio. It should also be noticed that Brito approached the expression of a complex self with certain psychological-metaphysical underpinnings, informed in this case by the theories of Jung and his followers. In the painted self-portraits, often Catholicism provides the means to structure a self-identity, as Jung theories do in this piece.

One of the most plain, yet haunting boxes by Maria Brito is The Room Upstairs: Self Portrait with Two Friends in the collection of the Lowe Art Museum in Coral Gables, Florida. Barely 15 1/2 x 11 1/4 inches, this box is divided into two unequal compartments. The lower section shows a partial domestic interior suggested by a white door set in the middle of a two-toned blue wall and preceded by checkered floor. The smaller upper compartment, more of an attic than a second floor, houses three black and white images of young girls, one split down the middle, and a partly hidden butterfly.

The piece touches on a number of Brito’s themes of the 1980s: domestic interiors, childhood memories, and fragmented self. The theme of childhood memories was inspired in part by interaction with her children, which brought back memories of her own childhood. Not surprisingly these real/fictional memories are often presented in the context of domesticity. In this piece, the sense of memory is evoked by the emptiness of the domestic interior, the fact that although I have described the lower part as an interior, it could also be seen as an exterior, the combination of color and black and white images, and the incongruous butterfly. The content of the memory offers a discourse on the self, made all the more poignant by the split in the self-portrait and the knowledge that the friends are imaginary. The elements of desire, imagination, and fragmentation give the memory a bittersweet taste and posit an expansive view of self. The enlarged and out of place butterfly, which to Brito symbolizes frailty and freedom, offers a happy note to the composition.

Wanting to expand into real space Maria Brito early on began to work on human scale mixed media sculptures. The use of found objects, her vocabulary of forms, and the content of her larger pieces is similar to that of the boxes, except that the theme of domestic interiors became more prevalent in the tableaux.

Boxes

On the Folly of Cleopatra

Memories of the Future

In the modern world, the representation of secular domestic interiors as artistic subject begins in Holland in the seventeenth century, best seen in the paintings of Johannes Vermeer. His carefully constructed interiors, as seemingly “realistic” and transparent as they are in style, offer a vision more than a window into Dutch society of that time: wealthy, cultured, and serene. Since then the representation and later also the literal construction of domestic interiors to narrate or symbolize social issues, personal experiences, psychological states, or metaphysical speculation has become an artistic tradition.

In the 1980s, when Maria Brito began her artistic career, artists who constructed, photographed, and painted tableaux or dramatic scenes of domestic interiors were on the rise. The 1984 exhibition Anxious Interiors, at the Laguna Beach Museum in California showed ten assemblage artists and nineteen photographers exploring the subject in question. In the catalogue “Introduction,” the curator Elaine K. Dines states “the domestic interior was selected because the home was repeatedly used as a reference site by the artists.” [x] She also explained that what the artists have in common is their fabrication of dramatic situations exploring real and surreal concerns, which evoke anxiety. The exhibition’s title and the curator’s overall description of the works have strong affinities with Maria Brito’s mixed media sculptures in question. Her “anxious interiors” would have been very much at home in that exhibition.

Maria Brito began to use the theme of domestic interiors early in her career. She used discarded wood and household goods, debris she found in neighborhood trash piles, to suggest a domestic environment. By 1985, her mixed media sculptures increased to human scale and the construction of fragmented interiors reached maturity in works such as Woman Before a Mirror(1983), The Room of the Two Maria’s (1984), and Come Play with Us: Childhood Memories (1984). In these pieces domestic interiors are minimally suggested by the use of partial walls, a piece of wood floor, and housewares. Her interiors reached a high point in the early 1990s with pieces like Whitewash(1990), El Patio de mi Casa (1991), and Merely a Player (1993).

An outstanding example of Maria Brito’s early life size constructions is Woman Before a Mirror, which suggests a fragment of a woman’s bedroom. The work is mostly made of found objects and consists of a floor made of unfinished wood planks, a small cabinet, and a wall with worn out wallpaper, on which hangs various objects: an oval mirror, part of which is transparent and one can see small objects floating in space, a small ledge with two clear glass jars, each containing a photo of a monarch butterfly, and hanging from the ledge there is a hand mirror with the face (photocopy) of the artist. The cabinet has pinned on the inner side religious stamps and is lined with purple cloth. Inside are small hand mirrors with photocopies of the artist’s face on the reflective side and a shell.

Brito’s tableau was inspired by Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror, which itself is a variation on the woman-before-a-mirror theme that Titian pioneered in the sixteenth century. Brito’s version acknowledges its sources in its title and the presence of mirrors, but there similarities end. Unlike the European tradition of representing women looking into mirrors to signify vanity and/ or sensuality as seen from a male gaze, Brito’s represents a thoroughly feminine space and feeling through the handling of materials and use of symbolism. She also translated a theme associated with painting to assemblage. In Brito’s Woman Before a Mirror, the woman, although absent, is implied in the title and suggested by the feminine looking wallpaper, the small cabinet with its religious stamps and shell, the monarch butterflies, and the mirrors with photocopies of the artist’s face on its supposed reflective surface. The absence/presence duality plays a major role in Brito’s interiors, where there is an absence of the human figure, yet there is a strong feminine presence. She takes away the female body, the object of men’s delectation as the theme is traditionally represented, but asserts its presence through every detail of the construction. It is not about pretty faces, sensual bodies, and the male gaze, but about psychology, interiority, and identity.

Its iconography can be partly interpreted in light of the artist’s intention as it is known from interviews. “ I thought of the small cabinet as a metaphor for a woman. This was to contain personal memories. Woman as a container.” [xi] That, according to Brito, is the work’s main theme. Other outstanding objects in the work, which may be seen as sub-themes are the extensive use of mirrors and the motif of the monarch butterflies. “The idea was prompted by the thought that mirrors are actually receptacles which contain the images and memories of those who were once reflected on them.” [xii] Brito endows mirrors with memory. The monarch butterfly is meant to suggest a “delicate freedom.” The issues of memory, tenuous freedom, and woman as a container recur in the work of Maria Brito and one may find their early mature expressions in Woman Before a Mirror.

Another major work of 1984, a very productive year for Brito, is Come Play with Us (Childhood Memories). This is a more complex tableau than Woman Before a Mirror in its construction and composition. The wall section is covered with flowery wallpaper on which are painted eyes covered with pieces of transparent gauze pinned to the wall. Behind the wall there is a large shadow box partly seen through half the surface of a framed mirror, which is made of clear plexiglass. Inside the shadow box are small babies hands, which appear to be luring the viewer to an uncertain infinite space, suggested by the use of mirrors reflecting other mirrors. Also on the wall is a frame replica in low relief of the actual piece. On the floor section in front of the wall is a structure suggesting a crib/cage. The floor of the crib/cage is lined with a pinkish flower pattern fabric and on top rest a rattle painted pink and a framed with a somewhat defaced photocopy of the artist’s adult face. One of the bars of the crib/cage is broken and provides access to the floor via a ladder. There, pieces of white wood allude to children’s alphabet cubes. Finally, there is a ladder with wheels reclining against the framed replica described above.

As the second part of the title indicates—Childhood Memories-- the work deals with childhood through the agency of memory. It is one of a number of works that were done about the time that Brito’s sons were entering their teenager years, prompting her to reflect on her childhood. Those reflections led in various directions, two dominant ones in this work are surveillance (eyes all over the wall) and fragile freedom or liberation (broken bar and ladder). The eyes, according to Brito, “ imply a ‘veiled’ type or surveillance or control, which is the overall theme of the piece.” [xiii] The sense of surveillance and control over the life of children, particularly girls, is very much part of the Cuban and Cuban-American culture in which Maria Brito grew up and this work offers a compelling expression of parental overprotection. Come Play with Us (Childhood Memories)also suggests that overprotection is not full proof and that there is the desire and possibility of liberation manifested by the broken bar in the crib/cage and the escape ladder. Entrapment by tradition, culture, and family and the possibility of liberation is a recurrent theme in Brito’s work.

The early 1980s mixed media sculpture that offers the most complex reflection on constructing a self-identity is The Room of the Two Marias. The work implies the corner of a room. On the left wall there is a mirror/chair hybrid. The back of the implied chair becomes a mirror that can be covered at will by a partially rolled up shade. According to the artist, the mirror in this case “reflects reality” while the blind represents, when used, “denial of reality.” On the right wall there is a framed recessed space with two shelves and a curtain that can be drawn at will. On the top shell rests a rock-like form made up of white-fired clay. In Brito’s iconography this object is a metaphor for the self. On the lower shell there are a series of empty glass jars, except one, which contains a piece of wood painted pink flesh color. Pink, the predominant color of this assemblage is used consciously to suggest femininity.

Directly above this recessed there is a shallower one, also painted pink, on which hang two masks cast on the artist’s face. One of the masks has a serene look to it, while the other is distorted. These masks, along with the title, bring up once again the theme of duality. In this case a duality of self, referring not so much to the traditional comic/tragic dynamics, but more like peace/rage. The distorted mask has pasted on the eye sockets color reproduction of eyes, which sideway glance is most telling. The eyes seem to be looking at the top of the mirror/chair/table, more specifically at a framed puzzle of the artist’s face made up of a b/w photocopy adhered to wood blocks. The puzzle is shown missing three parts, which lie next to it. This motif too suggests a search for self-identity, but one that is more complex than the duality shown in the masks.

Finally there is an altar-like structure attached to the upper corner of the room. Hanging from an area directly behind the altar are four small human silhouettes cut out of plywood. They represent Brito’s two sons, her former husband and her husband at that time. More dualities: self/family. At the top of the altar-like structure is a hand made out of cast plaster. There is a small, oval piece of cheesecloth attached to the palm of the hand suggesting an all-seeing hand/eye. This last motif refers to religion and supervision, the all-seeing eye of God.

While the individual objects described above have a more or less intentional and decipherable meanings, the overall iconography is much more elusive. The puzzle in the piece is perhaps the most telling symbol of an identity in the making, which pieces -- woman, family, and religion—exist in tight but uneasy accommodation.

In the 1990s Maria Brito honed her considerable skills in constructing her most acclaimed anxious interiors, such as Whitewash (1990), El Patio de Mi Casa (1991),and Merely a Player (1993). Generally, she worked on a larger scale than the 1980s and towards the later part of the 1990s further developed the interior theme or abandoned it altogether as social issues took precedent over more personal ones. In all, the nineties was a creative and highly productive decade for Brito.

Whitewash is a 5 x 5 feet cage with a wood floor, two solid walls, a third made up of heavy wired mesh, and the fourth a curtain. Through the wire mesh one can see a wall with six framed images of sky and clouds placed askew. To the right there is from top to bottom: a clock covered with paint, whitewashed like the rest of the room, a mirror with a collaged grinning mouth, lips painted red, and a shelf with a dark chalice-like object, on a white runner. The latter suggest a domestic altarpiece. In the middle of the caged room sits a red suitcase. On the ceiling, a white light reveals every detail, accentuates the few colored objects, and accentuates the title of the piece. The slightly opened door next to the shrine-like motif invites the viewer to move around the cage, explore its exterior, and peek in. The door actually connects two interior spaces, the latter barely suggested by another shelf holding fruits, below a drawing of a tree attached to the wall. Peeking through the door, the sense of expectation evoked by a detailed look at this interior culminates with the curious discovery that this side of the suitcase has been cut open in part and in it lays a naked baby doll.

The title of the piece, the careful choice and placement of the objects, and the fragmented and contracted space create a mood and suggest meaning. The artist and critics agree that Whitewash, at its most universal, signifies entrapment and the possibility of liberation. Beyond that, the artist has spoken eloquently about its intended meaning and critics have interpreted the nature of the entrapment and escape in various ways. First, what the artist had in mind:

Essentially the piece deals with entrapment. You are in this space where supposedly everything is provided for you, but you have other aspirations, not necessarily related to work, maybe more personal in nature. So the actual structure has a door that is partially opened as if to provoke the idea in the viewer that maybe there is escape. There is a suitcase smack in the middle of the floor of the piece … Inside the cage on the only solid wall there are framed sky images which are representative of what this person yearned for.[xiv]

Thus this assemblage, according to the author, was prompted by pending physical and psychological departure from the safety of the status quo in one’s life. Given that it was done about the time of Brito’s second divorce, Whitewash seems grounded in that experience.

As usual with Maria Brito’s work, personal experiences are embodied in fragmented compositions/spaces with juxtaposed objects that suggest multiple meanings. Chris Harold saw the piece as a statement on liberation. “Flight is evoked literally by the bright red suitcase that sits on the floor, presumably packed and ready for departure, and spiritually by the collection of paintings of clouds in bright blue sky on the back wall that stand for the double fantasy of freedom and flight.” [xv] To Carrie Przybilla, the main elements of the work are emblematic of “freedom or escape,” while the hidden battered doll in the suitcase “calls to mind an innocence and vulnerability, that although hidden and worn, is never completely lost.” [xvi]

I believe that Whitewash may also be seen as a representation of departure in the context of exile and/or immigration. Seen up-front, the piece is above all an “image” of departure: a close suitcase on the floor next to an open door, top by multiple scenes of sky seen up close, as from the window of an airplane. Then there is the content of the suitcase, a naked baby doll, suggesting the traveler is a child, a girl. In light of the artist’s experience and that of many other immigrants who left their homeland as children, without their parents, the central motif of this assemblage offers a powerful symbolic memory of the anxiety of departure and flying to an uncertain future.

Moreover, Whitewash can be seen as a moving expression of one of the most tragic episodes of the post 1959 Cuban migration to the United States: the so-called Operation Pedro Pan. This “operation” brought about 14,000 Cuban children without their parents to the United States in the early 1960s. [xvii] The parents feared the intentions of the Cuban Revolution regarding control of their children and decided to get them out as soon as possible with the hope of quickly reuniting with them in Miami. For many that proved impossible because leaving Cuba became more difficult. The whole enterprise was made possible originally through the combine efforts of James Baker, the headmaster of Havana’s Roston Academy, The American Embassy in Havana, and Monsignor Brian O. Walsh of the Miami archdiocese. Maria Brito was one of those children. In this light, the suitcase with the naked baby doll, the sky pictures, the chalice on the self, the mirror, and the covered clock take on a particular resonance alluding to a lonesome departure, absent parents, flight, the Catholic church, reflection/illusion, and arrested time. These are some of the very ingredients of the Peter Pan experience.

Finally, the title refers to the use of white paint to beautify or gloss over something, make it appear better than it really is. Given the overall tone of the piece as discussed above, the latter meaning seems more appropriate. Yet what has been whitewashed? Is it the sense of entrapment, the aspiration for something different, the possibility of escape, or painful memories? All of the above.

The same surrealist method of surprising juxtapositions that Maria Brito uses to arrange the objects in her mixed media sculptures, she also uses to organize space in her fragmented interiors. In Whitewash, two undetermined rooms are connected by a door; one can be entered, the other just look into, one is open, the other close. A similar but more dramatic juxtaposition of spaces occurs in El Patio de Mi Casa, today in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. On one side of a wall a crib sits on a crack grey floor, on the other side there is a dark pink kitchen cabinet and sink. These suggested bedroom and kitchen are on different leveled floors, which along with the separating wall suggest different realities and times. In El Patio… space and time collide in a memory. The latter element suggested not only by the fragmentary quality of the composition, but also by the sepia color scheme of the piece.

The artist, as in the case of Whitewash, has spoken about the overall content and in some cases the specific symbolism of certain motifs in El Patio de Mi Casa, providing a significant point of reference. According to Maria Brito, the title of her pieces usually come at the end, yet sometimes appear at the beginning of the process and guides it to some degree. In the case of El Patio de Mi Casa, the title came during the making of the piece as the artist found herself mentally humming a nursery rhyme, familiar to Cubans and Cuban-Americans of her generation, entitled El Patio de Mi Casa. Loosely translated the first part of the nursery rhyme goes: “My own backyard is not that particular, when it rains it gets wet like any other.” To the extent that nursery rhymes, one’s bed and backyard are representative of calming words and places of safety, the title strongly contrasts with the haunting bedroom part of the assemblage. The image of grey bed/crib with ominous tree shadows on its backboard, and a box (miniature house without roof) from which the dead tree trunk raises, is far from reassuring. Neither is the floor with its large dark crack. From this angle, the title seems quite ironic, while signaling that we are in the realm of childhood memories.

The bedroom area, according to Brito represents the past, childhood, while the kitchen stand for the present. They are literally and metaphorically connected by the water pipes, which along with the faucets are meant to suggest rain or collected water. “So water from the past was being channeled into the present and then collected in the sink of the actual kitchen. The water served to keep alive a little twig that was missing from the tree being born inside the bed.” She continued, “The present ended up being a kitchen, which makes perfect sense because it is a metaphor for change. It is one of the main places in a home where changes take place. It is where you process food, make it edible.” [xviii] Accordingly the kitchen represents not only the present, but change and transformation.

On the kitchen sink there are a number of objects that also connect past and present. There is a photo of Maria as a child next to a plaster cast of her adult face laid on a cutting board with a paring knife next to it. Layers of skin are being peeled off suggesting the removal of one’s many masks. There is a jar with a miniature house inside. And as mentioned by Brito, there is a twig on the sink from the tree on the bed. The kitchen in fact is invaded by elements of the past, old kitchen utensils, lamp, photos, etc., except the plaster cast of her adult face.

According to Maria Brito, the piece at its most personal is about breaking from the past. “The key to it is the plaster cast of my face whose layers of skin are being peeled off on a cutting board with a paring knife next to it. In essence, it is the breaking off from the past.” [xix] From the artist’s perspective, El patio de mi casa reflects the beginning of a new chapter in her life. After surviving a second divorce, beating a serious illness, and coming to terms with new aspects of herself, Maria Brito was ready to move on.

Given the complex iconography of the work, however, it has been interpreted in various ways. To Przybilla it represents the inescapability of one’s past and the persistence of memory, which named the piece. [xx] To the extent that the piece suggest the “inescapability of the past” and the “persistence of memory,” as well as displacement, it can also be seen in the context of immigration and biculturalism. To every exile and/or immigrant, a significant part of that past is a moment of rupture, a sense of “before and after,” suggested in this piece by the crack floor and dividing wall. An important part of the experience is also the sense of continuity between past and present, between the two Maria Brito’s in the photo and the mask, between the rain and faucet water, between the Cuban bedroom-backyard and Cuban-American kitchen. These views and feelings about the past, continuity, and identity as they regard the experience of exiles and immigrants, Cuban-American and others, are effectively expressed in El Patio de Mi Casa. It should also be noted that the emphasis place on water and its attribute as a source of life is a recurrent Catholic symbol, seen in countless religious images from the Middle Ages on. In this case water connects past and present, exterior and interior, as it gushes out of the faucet to feed the branch of an ancestral and seminal twig.

Thus far the most ambitious of Maria Brito’s complex psychological interiors is Merely a Player. This piece is an installation measuring15 by 17 feet with 9 feet-high walls. At its entrance there is a ragged sofa, an old light stand/table, some books with Spanish and English titles on the edge of a worn floor rug, and a framed picture of a townscape on one of two walls. This fragmentary but welcoming living room leads through a labyrinth of narrow corridors to a series of little chambers filled with intricate arrangements of Brito’s signature symbolic objects—doors, tables, washbasin-bed, tubes, shelf, mirror, jars, clock, plastic doll, childhood photos, light bulb, and masks. There is also a peephole show of a black and white film showing a child knocking on every door in a hallway, but none opens. The anxious journey through claustrophobic hallways is lined up with images, which, according to the artist, “follows a chronological sequence from childhood onward to where I am now.” [xxi]

Merely a Player has elicited various critical interpretations. Carol Damian sees it as a “laboratory of self-introspection,” expressing the dangers, entrapments, and fears of life’s journey. [xxii] Elisa Turner described it as one of Brito’s strongest and most complex works, “suggesting a series of shrines to barely remembered moments in that perilous, vulnerable passage from childhood to adulthood.” [xxiii] And to Anne Barclay Morgan, the piece “convincingly conveys a relevance beyond Brito’s history of displacement and loss.” [xxiv] This last comment, while pointing beyond the personal, reverts back to it. The general consensus is that Merely a Player offers a memorable expression of the related universal themes of the “journey of life” and the “rites of passage.” More or less following Catholic tradition, the journey is represented as fraught with danger (at least on an emotional and psychological level) and the rites of passage, to the extent that they are suggested by the shrine like configurations along the way, are symbolized and ritualized through given objects and images. Worth noting is Maria Brito’s innovative symbolization of the “journey of life” theme by placing it in the context of a domestic interior, rather than the usual outdoor setting found in traditional art.

In the 1980s, when Maria Brito began her artistic career, artists who constructed, photographed, and painted tableaux or dramatic scenes of domestic interiors were on the rise. The 1984 exhibition Anxious Interiors, at the Laguna Beach Museum in California showed ten assemblage artists and nineteen photographers exploring the subject in question. In the catalogue “Introduction,” the curator Elaine K. Dines states “the domestic interior was selected because the home was repeatedly used as a reference site by the artists.” [x] She also explained that what the artists have in common is their fabrication of dramatic situations exploring real and surreal concerns, which evoke anxiety. The exhibition’s title and the curator’s overall description of the works have strong affinities with Maria Brito’s mixed media sculptures in question. Her “anxious interiors” would have been very much at home in that exhibition.

Maria Brito began to use the theme of domestic interiors early in her career. She used discarded wood and household goods, debris she found in neighborhood trash piles, to suggest a domestic environment. By 1985, her mixed media sculptures increased to human scale and the construction of fragmented interiors reached maturity in works such as Woman Before a Mirror(1983), The Room of the Two Maria’s (1984), and Come Play with Us: Childhood Memories (1984). In these pieces domestic interiors are minimally suggested by the use of partial walls, a piece of wood floor, and housewares. Her interiors reached a high point in the early 1990s with pieces like Whitewash(1990), El Patio de mi Casa (1991), and Merely a Player (1993).

An outstanding example of Maria Brito’s early life size constructions is Woman Before a Mirror, which suggests a fragment of a woman’s bedroom. The work is mostly made of found objects and consists of a floor made of unfinished wood planks, a small cabinet, and a wall with worn out wallpaper, on which hangs various objects: an oval mirror, part of which is transparent and one can see small objects floating in space, a small ledge with two clear glass jars, each containing a photo of a monarch butterfly, and hanging from the ledge there is a hand mirror with the face (photocopy) of the artist. The cabinet has pinned on the inner side religious stamps and is lined with purple cloth. Inside are small hand mirrors with photocopies of the artist’s face on the reflective side and a shell.

Brito’s tableau was inspired by Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror, which itself is a variation on the woman-before-a-mirror theme that Titian pioneered in the sixteenth century. Brito’s version acknowledges its sources in its title and the presence of mirrors, but there similarities end. Unlike the European tradition of representing women looking into mirrors to signify vanity and/ or sensuality as seen from a male gaze, Brito’s represents a thoroughly feminine space and feeling through the handling of materials and use of symbolism. She also translated a theme associated with painting to assemblage. In Brito’s Woman Before a Mirror, the woman, although absent, is implied in the title and suggested by the feminine looking wallpaper, the small cabinet with its religious stamps and shell, the monarch butterflies, and the mirrors with photocopies of the artist’s face on its supposed reflective surface. The absence/presence duality plays a major role in Brito’s interiors, where there is an absence of the human figure, yet there is a strong feminine presence. She takes away the female body, the object of men’s delectation as the theme is traditionally represented, but asserts its presence through every detail of the construction. It is not about pretty faces, sensual bodies, and the male gaze, but about psychology, interiority, and identity.

Its iconography can be partly interpreted in light of the artist’s intention as it is known from interviews. “ I thought of the small cabinet as a metaphor for a woman. This was to contain personal memories. Woman as a container.” [xi] That, according to Brito, is the work’s main theme. Other outstanding objects in the work, which may be seen as sub-themes are the extensive use of mirrors and the motif of the monarch butterflies. “The idea was prompted by the thought that mirrors are actually receptacles which contain the images and memories of those who were once reflected on them.” [xii] Brito endows mirrors with memory. The monarch butterfly is meant to suggest a “delicate freedom.” The issues of memory, tenuous freedom, and woman as a container recur in the work of Maria Brito and one may find their early mature expressions in Woman Before a Mirror.

Another major work of 1984, a very productive year for Brito, is Come Play with Us (Childhood Memories). This is a more complex tableau than Woman Before a Mirror in its construction and composition. The wall section is covered with flowery wallpaper on which are painted eyes covered with pieces of transparent gauze pinned to the wall. Behind the wall there is a large shadow box partly seen through half the surface of a framed mirror, which is made of clear plexiglass. Inside the shadow box are small babies hands, which appear to be luring the viewer to an uncertain infinite space, suggested by the use of mirrors reflecting other mirrors. Also on the wall is a frame replica in low relief of the actual piece. On the floor section in front of the wall is a structure suggesting a crib/cage. The floor of the crib/cage is lined with a pinkish flower pattern fabric and on top rest a rattle painted pink and a framed with a somewhat defaced photocopy of the artist’s adult face. One of the bars of the crib/cage is broken and provides access to the floor via a ladder. There, pieces of white wood allude to children’s alphabet cubes. Finally, there is a ladder with wheels reclining against the framed replica described above.

As the second part of the title indicates—Childhood Memories-- the work deals with childhood through the agency of memory. It is one of a number of works that were done about the time that Brito’s sons were entering their teenager years, prompting her to reflect on her childhood. Those reflections led in various directions, two dominant ones in this work are surveillance (eyes all over the wall) and fragile freedom or liberation (broken bar and ladder). The eyes, according to Brito, “ imply a ‘veiled’ type or surveillance or control, which is the overall theme of the piece.” [xiii] The sense of surveillance and control over the life of children, particularly girls, is very much part of the Cuban and Cuban-American culture in which Maria Brito grew up and this work offers a compelling expression of parental overprotection. Come Play with Us (Childhood Memories)also suggests that overprotection is not full proof and that there is the desire and possibility of liberation manifested by the broken bar in the crib/cage and the escape ladder. Entrapment by tradition, culture, and family and the possibility of liberation is a recurrent theme in Brito’s work.

The early 1980s mixed media sculpture that offers the most complex reflection on constructing a self-identity is The Room of the Two Marias. The work implies the corner of a room. On the left wall there is a mirror/chair hybrid. The back of the implied chair becomes a mirror that can be covered at will by a partially rolled up shade. According to the artist, the mirror in this case “reflects reality” while the blind represents, when used, “denial of reality.” On the right wall there is a framed recessed space with two shelves and a curtain that can be drawn at will. On the top shell rests a rock-like form made up of white-fired clay. In Brito’s iconography this object is a metaphor for the self. On the lower shell there are a series of empty glass jars, except one, which contains a piece of wood painted pink flesh color. Pink, the predominant color of this assemblage is used consciously to suggest femininity.

Directly above this recessed there is a shallower one, also painted pink, on which hang two masks cast on the artist’s face. One of the masks has a serene look to it, while the other is distorted. These masks, along with the title, bring up once again the theme of duality. In this case a duality of self, referring not so much to the traditional comic/tragic dynamics, but more like peace/rage. The distorted mask has pasted on the eye sockets color reproduction of eyes, which sideway glance is most telling. The eyes seem to be looking at the top of the mirror/chair/table, more specifically at a framed puzzle of the artist’s face made up of a b/w photocopy adhered to wood blocks. The puzzle is shown missing three parts, which lie next to it. This motif too suggests a search for self-identity, but one that is more complex than the duality shown in the masks.

Finally there is an altar-like structure attached to the upper corner of the room. Hanging from an area directly behind the altar are four small human silhouettes cut out of plywood. They represent Brito’s two sons, her former husband and her husband at that time. More dualities: self/family. At the top of the altar-like structure is a hand made out of cast plaster. There is a small, oval piece of cheesecloth attached to the palm of the hand suggesting an all-seeing hand/eye. This last motif refers to religion and supervision, the all-seeing eye of God.

While the individual objects described above have a more or less intentional and decipherable meanings, the overall iconography is much more elusive. The puzzle in the piece is perhaps the most telling symbol of an identity in the making, which pieces -- woman, family, and religion—exist in tight but uneasy accommodation.

In the 1990s Maria Brito honed her considerable skills in constructing her most acclaimed anxious interiors, such as Whitewash (1990), El Patio de Mi Casa (1991),and Merely a Player (1993). Generally, she worked on a larger scale than the 1980s and towards the later part of the 1990s further developed the interior theme or abandoned it altogether as social issues took precedent over more personal ones. In all, the nineties was a creative and highly productive decade for Brito.

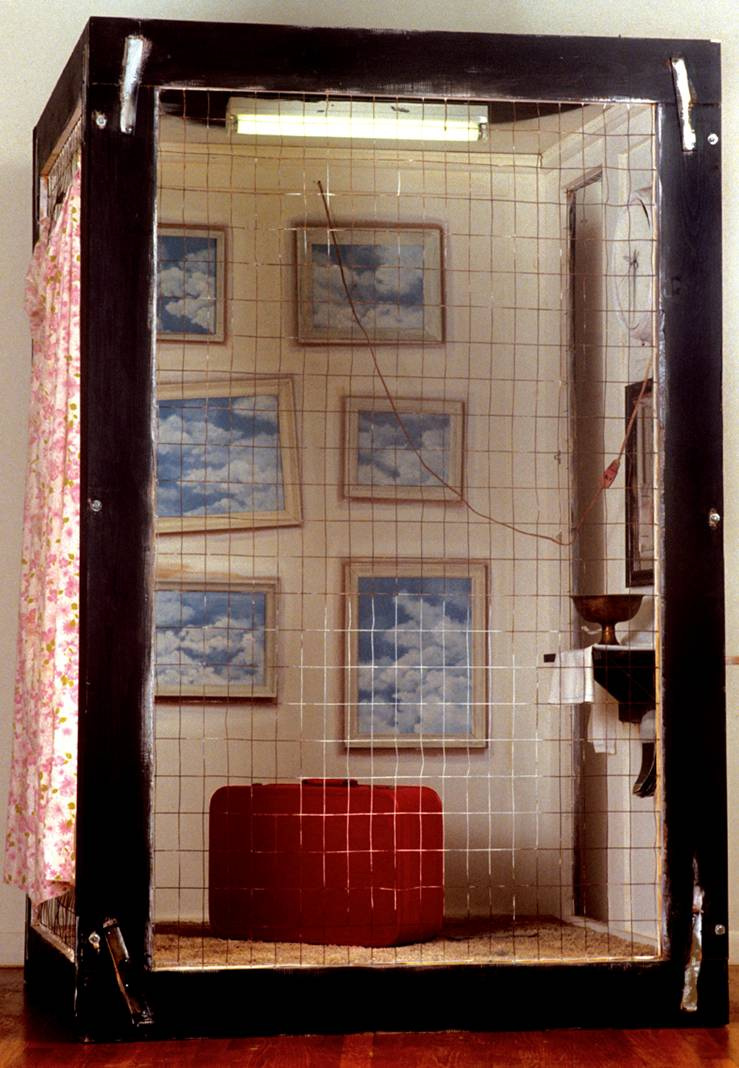

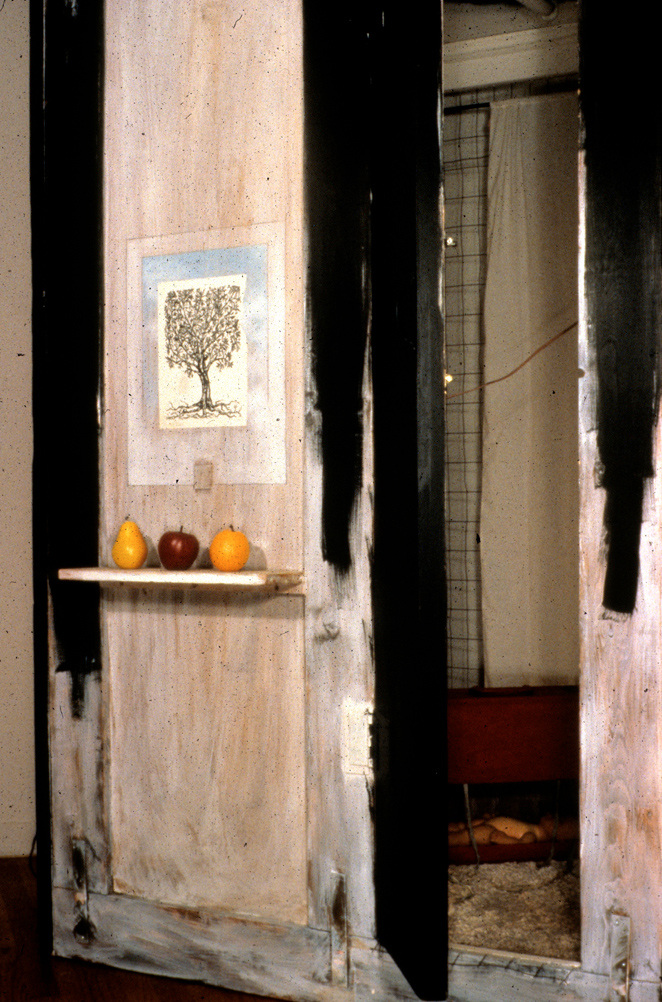

Whitewash is a 5 x 5 feet cage with a wood floor, two solid walls, a third made up of heavy wired mesh, and the fourth a curtain. Through the wire mesh one can see a wall with six framed images of sky and clouds placed askew. To the right there is from top to bottom: a clock covered with paint, whitewashed like the rest of the room, a mirror with a collaged grinning mouth, lips painted red, and a shelf with a dark chalice-like object, on a white runner. The latter suggest a domestic altarpiece. In the middle of the caged room sits a red suitcase. On the ceiling, a white light reveals every detail, accentuates the few colored objects, and accentuates the title of the piece. The slightly opened door next to the shrine-like motif invites the viewer to move around the cage, explore its exterior, and peek in. The door actually connects two interior spaces, the latter barely suggested by another shelf holding fruits, below a drawing of a tree attached to the wall. Peeking through the door, the sense of expectation evoked by a detailed look at this interior culminates with the curious discovery that this side of the suitcase has been cut open in part and in it lays a naked baby doll.

The title of the piece, the careful choice and placement of the objects, and the fragmented and contracted space create a mood and suggest meaning. The artist and critics agree that Whitewash, at its most universal, signifies entrapment and the possibility of liberation. Beyond that, the artist has spoken eloquently about its intended meaning and critics have interpreted the nature of the entrapment and escape in various ways. First, what the artist had in mind:

Essentially the piece deals with entrapment. You are in this space where supposedly everything is provided for you, but you have other aspirations, not necessarily related to work, maybe more personal in nature. So the actual structure has a door that is partially opened as if to provoke the idea in the viewer that maybe there is escape. There is a suitcase smack in the middle of the floor of the piece … Inside the cage on the only solid wall there are framed sky images which are representative of what this person yearned for.[xiv]

Thus this assemblage, according to the author, was prompted by pending physical and psychological departure from the safety of the status quo in one’s life. Given that it was done about the time of Brito’s second divorce, Whitewash seems grounded in that experience.

As usual with Maria Brito’s work, personal experiences are embodied in fragmented compositions/spaces with juxtaposed objects that suggest multiple meanings. Chris Harold saw the piece as a statement on liberation. “Flight is evoked literally by the bright red suitcase that sits on the floor, presumably packed and ready for departure, and spiritually by the collection of paintings of clouds in bright blue sky on the back wall that stand for the double fantasy of freedom and flight.” [xv] To Carrie Przybilla, the main elements of the work are emblematic of “freedom or escape,” while the hidden battered doll in the suitcase “calls to mind an innocence and vulnerability, that although hidden and worn, is never completely lost.” [xvi]

I believe that Whitewash may also be seen as a representation of departure in the context of exile and/or immigration. Seen up-front, the piece is above all an “image” of departure: a close suitcase on the floor next to an open door, top by multiple scenes of sky seen up close, as from the window of an airplane. Then there is the content of the suitcase, a naked baby doll, suggesting the traveler is a child, a girl. In light of the artist’s experience and that of many other immigrants who left their homeland as children, without their parents, the central motif of this assemblage offers a powerful symbolic memory of the anxiety of departure and flying to an uncertain future.

Moreover, Whitewash can be seen as a moving expression of one of the most tragic episodes of the post 1959 Cuban migration to the United States: the so-called Operation Pedro Pan. This “operation” brought about 14,000 Cuban children without their parents to the United States in the early 1960s. [xvii] The parents feared the intentions of the Cuban Revolution regarding control of their children and decided to get them out as soon as possible with the hope of quickly reuniting with them in Miami. For many that proved impossible because leaving Cuba became more difficult. The whole enterprise was made possible originally through the combine efforts of James Baker, the headmaster of Havana’s Roston Academy, The American Embassy in Havana, and Monsignor Brian O. Walsh of the Miami archdiocese. Maria Brito was one of those children. In this light, the suitcase with the naked baby doll, the sky pictures, the chalice on the self, the mirror, and the covered clock take on a particular resonance alluding to a lonesome departure, absent parents, flight, the Catholic church, reflection/illusion, and arrested time. These are some of the very ingredients of the Peter Pan experience.

Finally, the title refers to the use of white paint to beautify or gloss over something, make it appear better than it really is. Given the overall tone of the piece as discussed above, the latter meaning seems more appropriate. Yet what has been whitewashed? Is it the sense of entrapment, the aspiration for something different, the possibility of escape, or painful memories? All of the above.

The same surrealist method of surprising juxtapositions that Maria Brito uses to arrange the objects in her mixed media sculptures, she also uses to organize space in her fragmented interiors. In Whitewash, two undetermined rooms are connected by a door; one can be entered, the other just look into, one is open, the other close. A similar but more dramatic juxtaposition of spaces occurs in El Patio de Mi Casa, today in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. On one side of a wall a crib sits on a crack grey floor, on the other side there is a dark pink kitchen cabinet and sink. These suggested bedroom and kitchen are on different leveled floors, which along with the separating wall suggest different realities and times. In El Patio… space and time collide in a memory. The latter element suggested not only by the fragmentary quality of the composition, but also by the sepia color scheme of the piece.

The artist, as in the case of Whitewash, has spoken about the overall content and in some cases the specific symbolism of certain motifs in El Patio de Mi Casa, providing a significant point of reference. According to Maria Brito, the title of her pieces usually come at the end, yet sometimes appear at the beginning of the process and guides it to some degree. In the case of El Patio de Mi Casa, the title came during the making of the piece as the artist found herself mentally humming a nursery rhyme, familiar to Cubans and Cuban-Americans of her generation, entitled El Patio de Mi Casa. Loosely translated the first part of the nursery rhyme goes: “My own backyard is not that particular, when it rains it gets wet like any other.” To the extent that nursery rhymes, one’s bed and backyard are representative of calming words and places of safety, the title strongly contrasts with the haunting bedroom part of the assemblage. The image of grey bed/crib with ominous tree shadows on its backboard, and a box (miniature house without roof) from which the dead tree trunk raises, is far from reassuring. Neither is the floor with its large dark crack. From this angle, the title seems quite ironic, while signaling that we are in the realm of childhood memories.

The bedroom area, according to Brito represents the past, childhood, while the kitchen stand for the present. They are literally and metaphorically connected by the water pipes, which along with the faucets are meant to suggest rain or collected water. “So water from the past was being channeled into the present and then collected in the sink of the actual kitchen. The water served to keep alive a little twig that was missing from the tree being born inside the bed.” She continued, “The present ended up being a kitchen, which makes perfect sense because it is a metaphor for change. It is one of the main places in a home where changes take place. It is where you process food, make it edible.” [xviii] Accordingly the kitchen represents not only the present, but change and transformation.

On the kitchen sink there are a number of objects that also connect past and present. There is a photo of Maria as a child next to a plaster cast of her adult face laid on a cutting board with a paring knife next to it. Layers of skin are being peeled off suggesting the removal of one’s many masks. There is a jar with a miniature house inside. And as mentioned by Brito, there is a twig on the sink from the tree on the bed. The kitchen in fact is invaded by elements of the past, old kitchen utensils, lamp, photos, etc., except the plaster cast of her adult face.

According to Maria Brito, the piece at its most personal is about breaking from the past. “The key to it is the plaster cast of my face whose layers of skin are being peeled off on a cutting board with a paring knife next to it. In essence, it is the breaking off from the past.” [xix] From the artist’s perspective, El patio de mi casa reflects the beginning of a new chapter in her life. After surviving a second divorce, beating a serious illness, and coming to terms with new aspects of herself, Maria Brito was ready to move on.

Given the complex iconography of the work, however, it has been interpreted in various ways. To Przybilla it represents the inescapability of one’s past and the persistence of memory, which named the piece. [xx] To the extent that the piece suggest the “inescapability of the past” and the “persistence of memory,” as well as displacement, it can also be seen in the context of immigration and biculturalism. To every exile and/or immigrant, a significant part of that past is a moment of rupture, a sense of “before and after,” suggested in this piece by the crack floor and dividing wall. An important part of the experience is also the sense of continuity between past and present, between the two Maria Brito’s in the photo and the mask, between the rain and faucet water, between the Cuban bedroom-backyard and Cuban-American kitchen. These views and feelings about the past, continuity, and identity as they regard the experience of exiles and immigrants, Cuban-American and others, are effectively expressed in El Patio de Mi Casa. It should also be noted that the emphasis place on water and its attribute as a source of life is a recurrent Catholic symbol, seen in countless religious images from the Middle Ages on. In this case water connects past and present, exterior and interior, as it gushes out of the faucet to feed the branch of an ancestral and seminal twig.

Thus far the most ambitious of Maria Brito’s complex psychological interiors is Merely a Player. This piece is an installation measuring15 by 17 feet with 9 feet-high walls. At its entrance there is a ragged sofa, an old light stand/table, some books with Spanish and English titles on the edge of a worn floor rug, and a framed picture of a townscape on one of two walls. This fragmentary but welcoming living room leads through a labyrinth of narrow corridors to a series of little chambers filled with intricate arrangements of Brito’s signature symbolic objects—doors, tables, washbasin-bed, tubes, shelf, mirror, jars, clock, plastic doll, childhood photos, light bulb, and masks. There is also a peephole show of a black and white film showing a child knocking on every door in a hallway, but none opens. The anxious journey through claustrophobic hallways is lined up with images, which, according to the artist, “follows a chronological sequence from childhood onward to where I am now.” [xxi]

Merely a Player has elicited various critical interpretations. Carol Damian sees it as a “laboratory of self-introspection,” expressing the dangers, entrapments, and fears of life’s journey. [xxii] Elisa Turner described it as one of Brito’s strongest and most complex works, “suggesting a series of shrines to barely remembered moments in that perilous, vulnerable passage from childhood to adulthood.” [xxiii] And to Anne Barclay Morgan, the piece “convincingly conveys a relevance beyond Brito’s history of displacement and loss.” [xxiv] This last comment, while pointing beyond the personal, reverts back to it. The general consensus is that Merely a Player offers a memorable expression of the related universal themes of the “journey of life” and the “rites of passage.” More or less following Catholic tradition, the journey is represented as fraught with danger (at least on an emotional and psychological level) and the rites of passage, to the extent that they are suggested by the shrine like configurations along the way, are symbolized and ritualized through given objects and images. Worth noting is Maria Brito’s innovative symbolization of the “journey of life” theme by placing it in the context of a domestic interior, rather than the usual outdoor setting found in traditional art.

Interiors

Woman Before a Mirror, 1983

Come Play with Us, 1985

The Room of the Two Marias, 1984

Whitewash, 1990

Whitewash, detail

Merely A Player, 1993

After Merely a Player Maria Brito turned her attention to more social oriented works in the mid to late 1990s leading to some of her most poignant tableaus, such as Cuatro Pilares 1994, Trappings1995, Some Mean Well 1995, and Pero sin Amo 1999-2000. They have in common a critical view of the human condition, certain institutions, and events.

The earlier one, Cuatro Pilares (Four Pilars), is a large mixed media construction dealing with the subject of strict religious upbringing and its influence in forming an identity. At the center of the piece is a red chair situated inside a playpen along with a door, a pan, and tubes. The two central motifs, the chair and the playpen, allude to an individual present by its very absence, most likely female, and to entrapment/confinement respectively. The chair faces a window that limits the field of vision. “ I am trying to communicate with this piece how a young person, raised in the manner that I was, is only presented with one way of life.” [xxv] The view out the window is an image of Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin, where only Mary has not been white out. She represents the one way of life or model for young and adult Catholic women. Appropriately, the image is part of a banner, a standard, which along with the four pillars of the title, suggest church furnishings and something of their pomp. The pillars or posts, which are located at the four corners of the square assemblage, hold on their outside images of the four evangelists and inside, aimed at the playpen, bright clip lights. According to Brito the lights “are elements of vigilance. Those lights are related to the Catholic church as an institution, thus their bases suggest objects found in church, which I have changed to make them more aggressive.” [xxvi]

Indeed it is amazing how Brito turned a simple lullaby told to children in Cuba and probably throughout the Spanish world, “ Cuatro pilares tiene mi cama/cuatro angeles que la guardan” (Four pillars has my bed/ four angels that guard it), into an aggressive statement of vigilance and indoctrination. Damian has keenly observed, “The most traditional of prayers, told to children throughout the world with little thought of how frightening these creatures may actually appears and how they may encourage a child to be dependent of supernatural forces, becomes a metaphor for cultural and social influences and limitations.”[xxvii] At its most universal, Cuatro Pilares represents a cutting critique of the limitations placed on young women by religion at large, stemming from the specific experiences of a Cuban-American woman raised Catholic.

The following year, 1995, Maria Brito constructed another large, but closed form interior entitled Trappings, a frightening laboratory for human alteration. Curtains of clear vinyl and red painted wood panels, one side with steps and a false door, enclose an improbable apparatus carrying on a strange operation. A flesh-toned plaster cast of the artist’s face sits on a metal plate, placed on a wooden plank. Close to the mask, on one corner of the operation table, are vile tubes placed in a rough metal dispenser. Towards the chin of the mask is a vertical board with a central peephole, which only allows for a view of a cut out Madonna and Child inside a birdcage. On one wall are desiccated ceramic squares. These pieces signify layers of skin that are to be molded into masks—therefore concealing true identities—intended for later use on other potential beings. Acting as a lone witness is a light bulb precariously hanging on top of the mask/face.

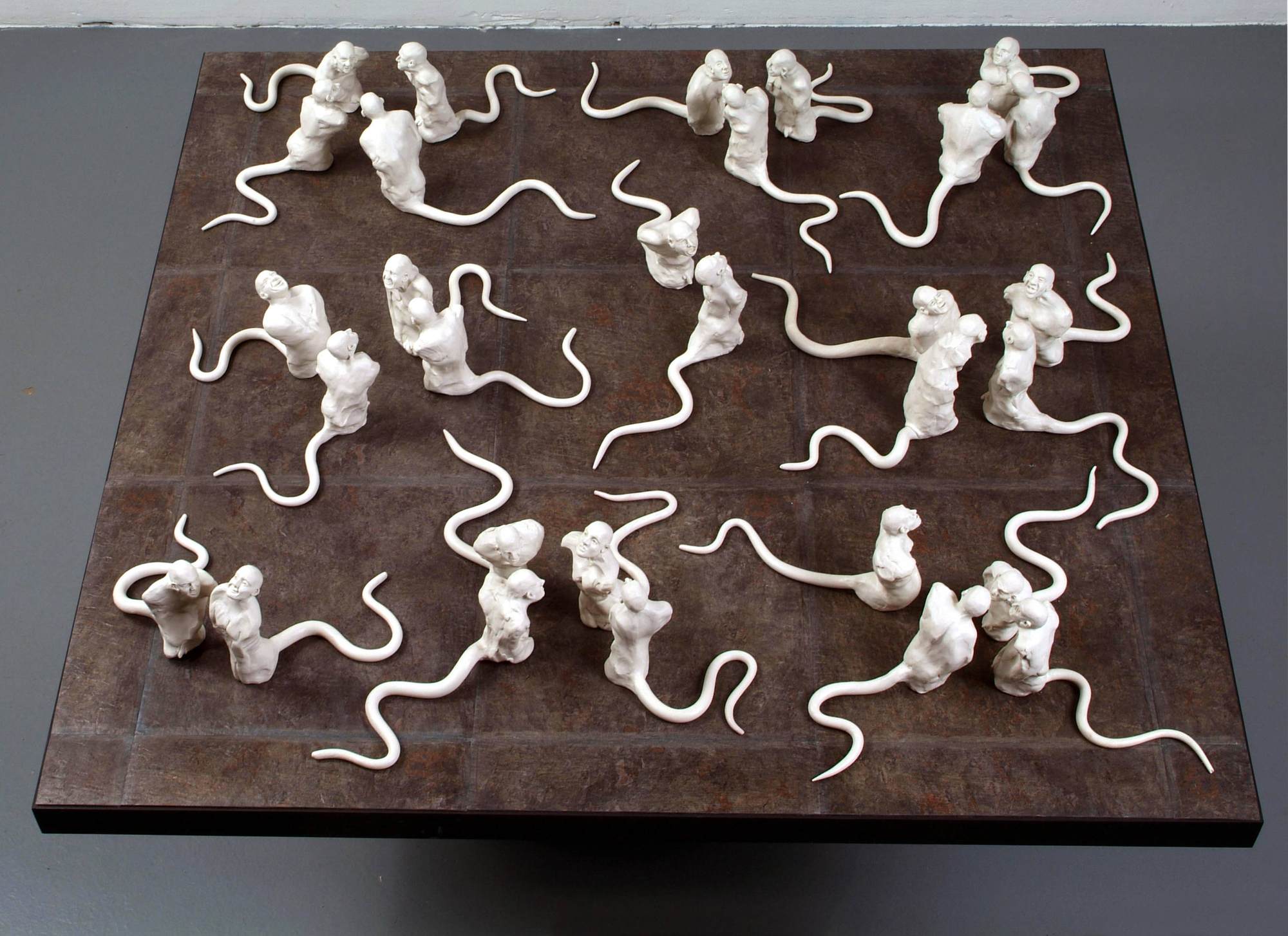

Trappings shares certain motifs with Cuatro Pilares: a female presence, tubes and containers, a directed view or look at the Virgin Mary, and bright dramatic light. The elements of limiting and crushing Catholic dogma, frightening vigilance, confinement, and the resulting draining of the life force are present in both. Trappings, however, is a complex work which content points in a number of directions. These directions are succinctly summarized by Dorothy Limouze: “ It encompasses statements on the unwilling transformation that an individual undergoes at the hands of social institutions; on artificiality, repression, and the lack of privacy; and on one’s true self and the lifeless substitutes that society imposes for the self.”[xxviii]