Juan A Martinez, 2012

A Cuban teenager from Santiago de Cuba arrived in NYC, where he would study art and become a prominent portrait painter in that city. His well-to-do family sent their youngest son to the United States to keep him out of harm’s way due to turbulent political times in the island. The year was 1868, the young man was Guillermo Collazo (1850-1896), and it was the beginning of Cuba’s First War of Independence. He was the first Cuban to study and practice art, successfully, in the United States. Others had come before him and many afterwards, but they were mostly formed artists by the time they arrived in the United States.

Fast-forward one hundred years and history repeats itself on a much larger scale. In the 1960s, an entire generation of Cubans came to the United States as teenagers, fleeing political turmoil. They studied art in this country, and in the last thirty years have become a part of the narrative, if seldom told, of contemporary American art. This is particularly the case with the so-called Miami Generation.

The term Miami Generation was coined in 1983 by the late Giulio V. Blanc (1955-1995), an art historian, critic, and curator, to title an exhibition of nine Cuban American artists he organized for the former Cuban Museum of Art and Culture, Miami. The term, which in my estimation applies to more artists than included in the exhibition, refers to Cuban-Americans who came of age in the 1960s and early 1970s, studied art partially or entirely in Miami colleges and universities, and emerged as artists in the late 1970s.

In the Preface for The Miami Generation: Nine Cuban-American Artists exhibition catalogue, Cynthia Jaffee McCabe (1943-1986), then a curator at the Hirshhorn Museum wrote: “It will be extremely interesting to watch these Cuban-American artists during the next decade. As more and more of them become known individually beyond the Miami-Dade region, one hopes and expects that, as their works develop, aesthetically, they will retain the special bicultural qualities which permeate this exhibition.” This essay looks at these artists’ careers thirty years later and offers a glimpse into McCabe’s prediction and hopes.

More specifically, the essay reviews the artists’ development, careers, and contributions to contemporary American art. They are: Mario Bencomo (1953-), Maria Brito (1947-), Humberto Calzada (1944-), Pablo Cano (1961-), Emilio Falero (1947), Fernando García (1945-1989), Juan González (1942-1993), Carlos Maciá (1951-1994) and César Trasobares (1949-).

Fast-forward one hundred years and history repeats itself on a much larger scale. In the 1960s, an entire generation of Cubans came to the United States as teenagers, fleeing political turmoil. They studied art in this country, and in the last thirty years have become a part of the narrative, if seldom told, of contemporary American art. This is particularly the case with the so-called Miami Generation.

The term Miami Generation was coined in 1983 by the late Giulio V. Blanc (1955-1995), an art historian, critic, and curator, to title an exhibition of nine Cuban American artists he organized for the former Cuban Museum of Art and Culture, Miami. The term, which in my estimation applies to more artists than included in the exhibition, refers to Cuban-Americans who came of age in the 1960s and early 1970s, studied art partially or entirely in Miami colleges and universities, and emerged as artists in the late 1970s.

In the Preface for The Miami Generation: Nine Cuban-American Artists exhibition catalogue, Cynthia Jaffee McCabe (1943-1986), then a curator at the Hirshhorn Museum wrote: “It will be extremely interesting to watch these Cuban-American artists during the next decade. As more and more of them become known individually beyond the Miami-Dade region, one hopes and expects that, as their works develop, aesthetically, they will retain the special bicultural qualities which permeate this exhibition.” This essay looks at these artists’ careers thirty years later and offers a glimpse into McCabe’s prediction and hopes.

More specifically, the essay reviews the artists’ development, careers, and contributions to contemporary American art. They are: Mario Bencomo (1953-), Maria Brito (1947-), Humberto Calzada (1944-), Pablo Cano (1961-), Emilio Falero (1947), Fernando García (1945-1989), Juan González (1942-1993), Carlos Maciá (1951-1994) and César Trasobares (1949-).

Today’s Miami--a metropolis, banking center, gateway to Latin America, and exceedingly multicultural society--began to take shape in the 1980s and so did its contemporary art scene. By mid-decade the Dade County government founded the Center for the Fine Arts (a non-collecting exhibition museum) and a robust Art in Public Places program. The former is now a collecting institution with a new name, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, and a new building.

The Cuban community acquired a permanent locale in Little Havana for its Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture. Florida International University opened its Art Gallery, today the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, and developed its B.F.A. program. Towards the end of the decade, the Miami-Dade Public School system, along with Miami-Dade College, founded the renowned New World School of the Arts. Older institutions such as the Lowe Art Museum, the Bass Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (MOCA) also contributed to the budding art infrastructure of the city. Art galleries multiplied, mostly concentrated in Bal Harbor and Coral Gables. Media coverage of art exhibitions and events was provided by The Miami News, The Miami Herald, and El Nuevo Herald, which published regular art reviews and news.

The artists under consideration began to exhibit in Miami in the late 1970s and came to prominence in the 1980s, benefitting from the aforementioned developments and contributing to the nascent art scene. The growing political and economic power of Miami Cubans in the 1980s and the expansion of Cuban culture brought about by the Mariel Boatlift exodus of 1980 also played a role in the emergence of this generation of artists.

Specifically, three alternative spaces, all in downtown Miami, proved essential: the Bacardi Art Gallery directed by Juan Espinosa (born 1940) and located in their former headquarters on Biscayne Blvd.; the Main Miami-Dade Public Library art division led by Margarita Cano (1932-) and formerly housed in Bay Front Park, and the Frances Wolfson Art Gallery of Miami Dade College, Wolfson Campus, headed by Sheldon M. Lurie.

On the commercial side, Gallery at 24, Forma, and Meeting Point galleries represented a number of these artists and contributed to their initial exposure. A major event in that process was the Cuban Museum’s 1983 The Miami Generation: Nine Cuban-American Artists exhibition. The museum’s leadership was mostly interested in exhibitions of pre-1959 Cuban art, however it sponsored a few significant exhibitions on the art of Cuban-Americans in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The works of art included in the exhibition are mature pieces that provide a good representation of what these artists were doing in the 1980s. To begin with the painters, Bencomo’s Insular Night: Invisible Gardens, 1983 (Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida) is his first series of paintings inspired by poetry, in this case José Lezama Lima’s (1910-1976) expansive poem of the same title, and are abstract representations of the artist’s journey from Cuba to the United States via Spain. Tracing the trajectory out of Cuba, that leap into the void, is a recurrent theme in the work of Cuban-Americans.

Another major series of that decade is the Wind paintings, created in reaction to Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine, on April 1986, and inspired by Vincent Van Gogh’s (1863-1890) Starry Night, 1888 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York). An outstanding painting from that series is Cobalt Wind, 1986 (Collection of Maria Justo, Coconut Grove, Florida), whose sparse image possesses a strange foreboding beauty. Bencomo’s abstract expressionist style contrasts with the taut illusionism practiced by the rest of the painters participating in the exhibition.

Early on Calzada developed his favorite motif, the nineteenth century homestead of a white and wealthy Cuban criollo class, which he painted in a Precisionist-like realism, and turned into a rich and flexible symbol of nostalgia, ruins, and reconstruction over the years. A fine early example is La reja, 1979 (Private collection, Miami, Florida), of the nostalgia period and Planning the Eclipse, 1990 (Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, Florida) when the Cuban colonial homestead turns into ruin.

Falero’s illusionistic paintings with collage like composition, where two or more incongruous realities meet were already well developed in the 1970s, as seen in major works like The Visit, 1973 (Private collection, Miami, Florida) and Meninas and Industrial Landscape, 1974 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Mestre, Miami, Florida). In the former, Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) meets Pablo Picasso (1181-1973) and in the latter, Velazquez crashes the Industrial Age. The contrast between the different views of man and the world signal not only rupture, but more importantly continuities.To Falero, times change, but not humanity.

In the 1980s, his compositions become more complex, as seen in Findings, 1983 (Collection of Dr. Nunzio Mainieri, Coral Gables, Florida), shown at The Miami Generation exhibition. In this case, the image is unusually foreboding, showing a bulldozer about to dump red earth on an unsuspecting Velazquez’s child, who holds one of a pair of metal feet, borrowed from René Magritte (1989-1967). By mid-1980s, he developed a series of expressionistic paintings where Velazquez meets Jasper Johns (1930-), like Mariana and Flag, 1985 (Collection of the artist). In these paintings, his Spanish heritage meets his American upbringing.

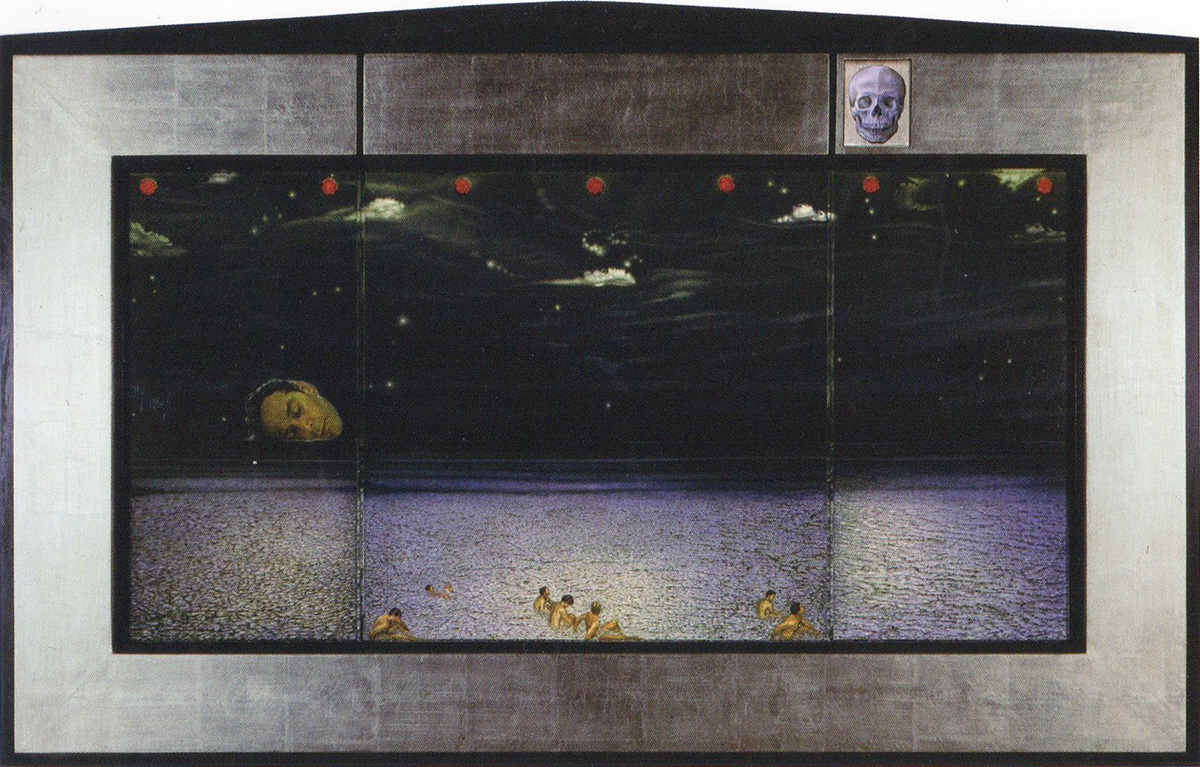

Gonzalez, like his friend Falero, was an early post modernist who often appropriated historical art, particularly from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, to visualize his own experience. Nativity, 1979 (Collection of Hal and Susan Einstein, New York) shown at The Miami Generation exhibition, quotes the nativity scene from Hugo Van der Goes (1440-1482), The Portinari Altarpiece, 1475 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy), to symbolize his birth. On the other end, Sea of Tears, 1987 (Collection of Maria and Daniel Schleifman, New York), is Gonzalez’s somber meditation on death and the AIDS epidemic. His head lies, in the manner of Constantin Brancusi’s (1876-1957) Sleeping Muse, 1910 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York), over a moonlit ocean at night. In the top part of the trompe l' oeil frame a drawn skull reigns.

Macía was a multimedia artist involved with collages, paintings, drawings, prints, and books. He is known for highly illusionistic “Façade” paintings, such as Mascher Street Façade, 1982 (location unknown), informed by Pop and Graffiti art. He was also represented in The Miami Generation show by etchings, like Basic Colors, 1983 (location unknown), inspired by Renaissance and Baroque art and his interest in theology.

In the early 1980s, Cano was involved with painting, collage, and book making. Cano’s La Sebastiana, 1983 (Collection of John and Lauren Oramas, Miami, Florida), a major early work, included in The Miami Generation exhibition, is a large collage presenting an allegorical and suffering view of Cuba as St. Sebastian(a). As with others in this group, Cano referred at times to his Cuban heritage through Catholic imagery.

As the decade progressed, his work turned to assemblages of found objects, and then to marionettes, as seen in Florabel Marionette Theater, 1985 (Collection of the artist). Since then, his work has doubled as performance pieces and sculpture.

A master of mixed media sculpture, Maria Brito’s inclusion in the exhibition, Woman Before a Mirror, 1983 (Collection of the artist), reclaims a theme going back to Titian (1485-1576), but from a woman’s point of view. She represents woman as subject, rather than object. More tableaux followed in the 1980s with the theme of self-exploration as Cuban-American woman, mother, wife, and human being, as in The Room of the Two Marias, 1984 (Collection of the artist), and Self-Portrait, 1989 (Collection of Arturo and Liza Mosquera, Miami, Florida). The latter is a curious assemblage of a wooden wheelchair, a dry branch, a armor on fire, and a small cage as head. Brito’s symbolic approach to self-portraiture invites questions and projections, but no definite interpretation.

Lastly, García and Trasobares share an interest in conceptual art and engaging with the community. García was represented in the show by one of his most poetic pieces, A Martí 1983 (Private collection, Miami, Florida), which consisted of a mirror with the outline of the Cuban flag etched in it and reflecting a quote from an essay José Martí (1853-1895) wrote on Michelangelo (1475-1564) ,written backwards on the opposite wall.

Martí, the apostle of Cuban independence, has been extensively quoted in Cuba and the Exile community for his political writings, yet García chose to focus on his least known line of writing, art criticism, which fitted perfectly with the site. In his brief, but productive career, García’s work showed a range of concerns from post-minimalism to works engaging Miami’s civic life.

Among his most recognized pieces are Holiday Spheres, 1985 (location unknown), consisting of weather balloons covered in brightly colored symbols and floated over the Miami-Dade Cultural Center during its opening; 10,865, 1980 (Miami-Dade County Public Library, Miami, Florida) a collage using the local media to document the Mariel Boatlift in real time; Anti-Bilingual Bigot, 1987 an ephemeral installation done in collaboration with Carlos Alfonzo (1950-1991), offering biting commentary on Miami’s “language wars” of that decade; and Making Purple, 1988, a neon piece at the Okeechobee Metrorail Station, which is part of the Miami-Dade’s Art in Public Places program.

Trasobares’s exhaustive exploration of the Cuban and Cuban-American popular rite of passage, the Quinceñera, was well represented in The Miami Generation show with pieces such as Les Demoiselles de la Petite Havanne, 1983 (Collection of the artist) and Quinceñera Club Kick Back Officer, 1978 (Perez Art Museum Miami, Florida, Gift of Richard and Ruth Shack). Using collages, boxes, and performances, Trasobares parodied these lavish coming out parties while keeping an anthropologist’s eye on issues of class, aesthetics, and the weight of traditions in the Miami Cuban exile community.

By the late 1980s, these artists had kept a constant presence in South Florida through participation in collective and personal exhibitions from West Palm Beach to Miami, including the Norton Gallery of Art, West Palm Beach, the Museum of Art, Ft. Lauderdale, MOCA, and the Center for the Fine Arts (now the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, Florida). A look at the art reviews of Ellen Edwards and Helen Kohen in The Miami Herald, Rafael Casalins in El Nuevo Herald, Lillian Dobbs and Paula Harper in the now defunct Miami News, and the catalogue essays and magazine articles by Ricardo Pau-Llosa and others reveal that these artists were hot; individually they caught the attention of these and other art critics who wrote from positive to glowing reviews of their art.

The 1980s rise of the concept of multiculturalism and the national interest in the rapidly growing Hispanic (soon to be known as Latino) population projected Miami into the national conversation about the importance of the Hispanic presence in the United States. This new attitude was partly responsible for a number of major traveling exhibitions in which artists of the Miami Generation were well represented. The most relevant exhibition of that decade was Fuera de Cuba/Outside of Cuba, 1987-1989. Organized by Ileana Fuentes Pérez, Graciella Cruz-Taura, and Ricardo Pau- Llosa, the exhibition opened at Rutger’s State University Jane Zimmerli Art Museum, March 22-May 26, 1987 and travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Arts, New York City, June 25-August 2; Miami University Art Museum, Oxford, Ohio, October 16-December 20; Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, July 15-September 8, 1988; Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, Florida, October 5-December 4; and New Visions Gallery of Contemporary Art, Atlanta, Georgia, March 20-April 19, 1989. It included forty-eight artists and had a substantial catalogue.

The Cuban community acquired a permanent locale in Little Havana for its Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture. Florida International University opened its Art Gallery, today the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, and developed its B.F.A. program. Towards the end of the decade, the Miami-Dade Public School system, along with Miami-Dade College, founded the renowned New World School of the Arts. Older institutions such as the Lowe Art Museum, the Bass Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (MOCA) also contributed to the budding art infrastructure of the city. Art galleries multiplied, mostly concentrated in Bal Harbor and Coral Gables. Media coverage of art exhibitions and events was provided by The Miami News, The Miami Herald, and El Nuevo Herald, which published regular art reviews and news.

The artists under consideration began to exhibit in Miami in the late 1970s and came to prominence in the 1980s, benefitting from the aforementioned developments and contributing to the nascent art scene. The growing political and economic power of Miami Cubans in the 1980s and the expansion of Cuban culture brought about by the Mariel Boatlift exodus of 1980 also played a role in the emergence of this generation of artists.

Specifically, three alternative spaces, all in downtown Miami, proved essential: the Bacardi Art Gallery directed by Juan Espinosa (born 1940) and located in their former headquarters on Biscayne Blvd.; the Main Miami-Dade Public Library art division led by Margarita Cano (1932-) and formerly housed in Bay Front Park, and the Frances Wolfson Art Gallery of Miami Dade College, Wolfson Campus, headed by Sheldon M. Lurie.

On the commercial side, Gallery at 24, Forma, and Meeting Point galleries represented a number of these artists and contributed to their initial exposure. A major event in that process was the Cuban Museum’s 1983 The Miami Generation: Nine Cuban-American Artists exhibition. The museum’s leadership was mostly interested in exhibitions of pre-1959 Cuban art, however it sponsored a few significant exhibitions on the art of Cuban-Americans in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The works of art included in the exhibition are mature pieces that provide a good representation of what these artists were doing in the 1980s. To begin with the painters, Bencomo’s Insular Night: Invisible Gardens, 1983 (Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida) is his first series of paintings inspired by poetry, in this case José Lezama Lima’s (1910-1976) expansive poem of the same title, and are abstract representations of the artist’s journey from Cuba to the United States via Spain. Tracing the trajectory out of Cuba, that leap into the void, is a recurrent theme in the work of Cuban-Americans.

Another major series of that decade is the Wind paintings, created in reaction to Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine, on April 1986, and inspired by Vincent Van Gogh’s (1863-1890) Starry Night, 1888 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York). An outstanding painting from that series is Cobalt Wind, 1986 (Collection of Maria Justo, Coconut Grove, Florida), whose sparse image possesses a strange foreboding beauty. Bencomo’s abstract expressionist style contrasts with the taut illusionism practiced by the rest of the painters participating in the exhibition.

Early on Calzada developed his favorite motif, the nineteenth century homestead of a white and wealthy Cuban criollo class, which he painted in a Precisionist-like realism, and turned into a rich and flexible symbol of nostalgia, ruins, and reconstruction over the years. A fine early example is La reja, 1979 (Private collection, Miami, Florida), of the nostalgia period and Planning the Eclipse, 1990 (Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, Florida) when the Cuban colonial homestead turns into ruin.

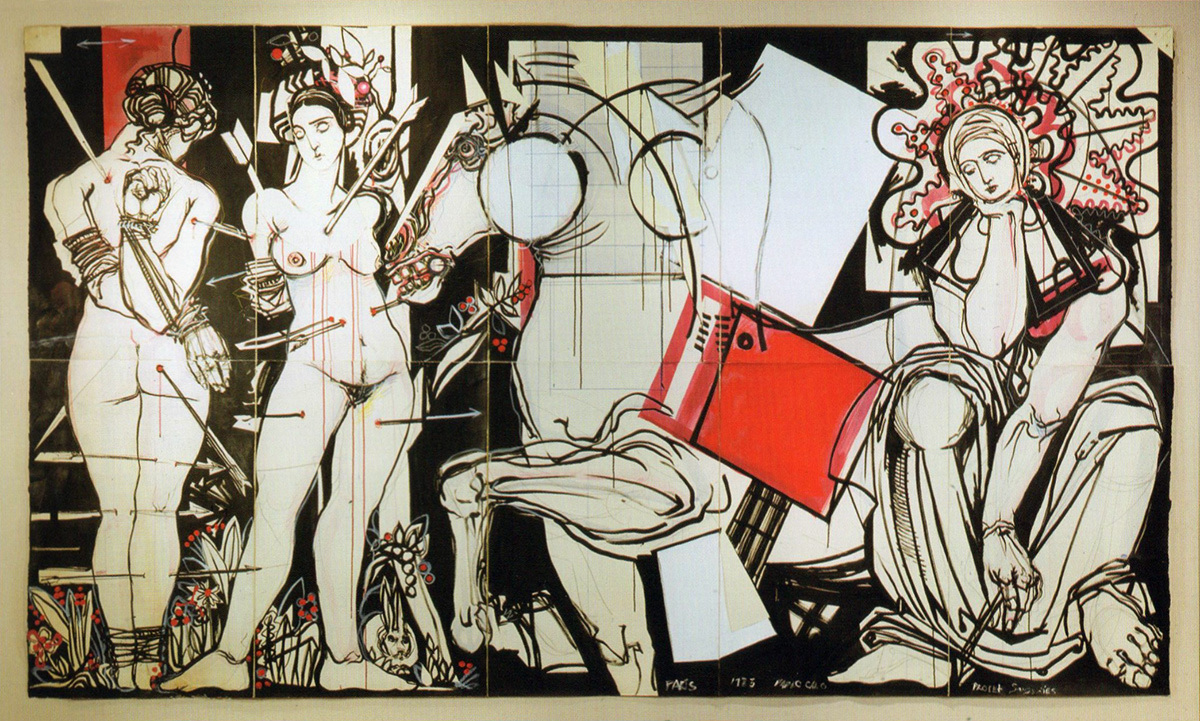

Falero’s illusionistic paintings with collage like composition, where two or more incongruous realities meet were already well developed in the 1970s, as seen in major works like The Visit, 1973 (Private collection, Miami, Florida) and Meninas and Industrial Landscape, 1974 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Mestre, Miami, Florida). In the former, Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) meets Pablo Picasso (1181-1973) and in the latter, Velazquez crashes the Industrial Age. The contrast between the different views of man and the world signal not only rupture, but more importantly continuities.To Falero, times change, but not humanity.

In the 1980s, his compositions become more complex, as seen in Findings, 1983 (Collection of Dr. Nunzio Mainieri, Coral Gables, Florida), shown at The Miami Generation exhibition. In this case, the image is unusually foreboding, showing a bulldozer about to dump red earth on an unsuspecting Velazquez’s child, who holds one of a pair of metal feet, borrowed from René Magritte (1989-1967). By mid-1980s, he developed a series of expressionistic paintings where Velazquez meets Jasper Johns (1930-), like Mariana and Flag, 1985 (Collection of the artist). In these paintings, his Spanish heritage meets his American upbringing.

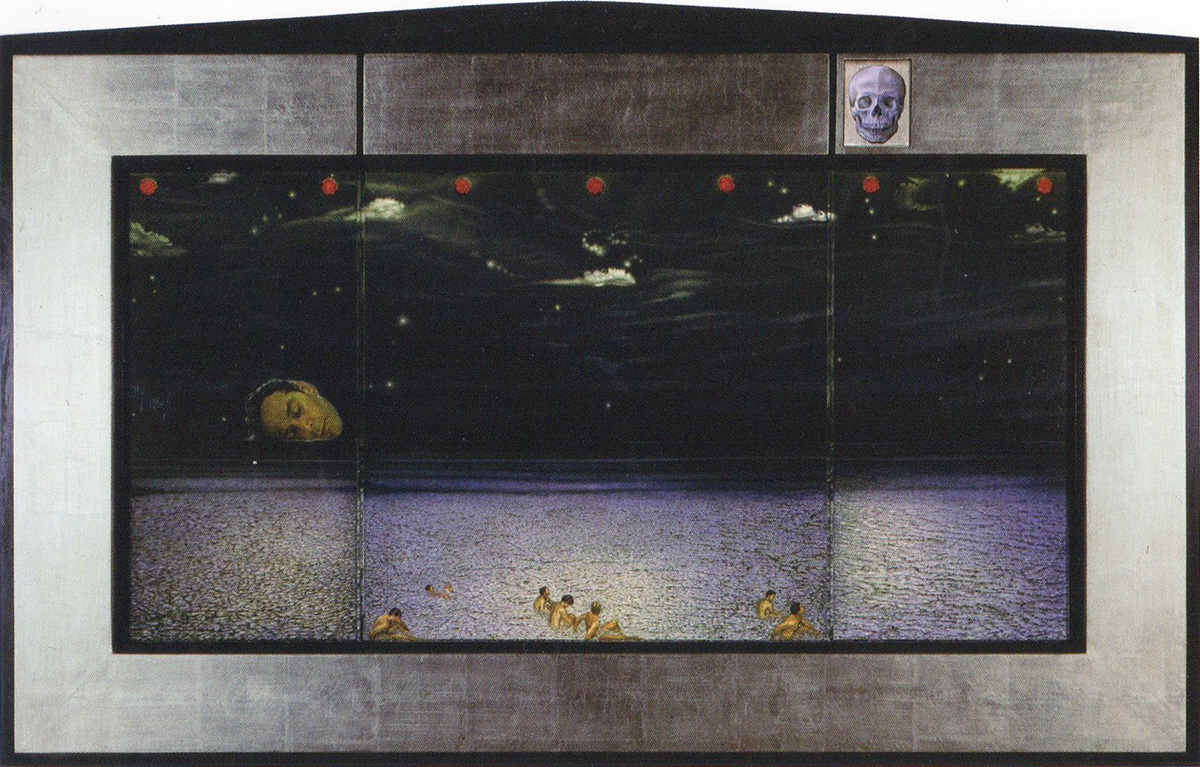

Gonzalez, like his friend Falero, was an early post modernist who often appropriated historical art, particularly from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, to visualize his own experience. Nativity, 1979 (Collection of Hal and Susan Einstein, New York) shown at The Miami Generation exhibition, quotes the nativity scene from Hugo Van der Goes (1440-1482), The Portinari Altarpiece, 1475 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy), to symbolize his birth. On the other end, Sea of Tears, 1987 (Collection of Maria and Daniel Schleifman, New York), is Gonzalez’s somber meditation on death and the AIDS epidemic. His head lies, in the manner of Constantin Brancusi’s (1876-1957) Sleeping Muse, 1910 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York), over a moonlit ocean at night. In the top part of the trompe l' oeil frame a drawn skull reigns.

Macía was a multimedia artist involved with collages, paintings, drawings, prints, and books. He is known for highly illusionistic “Façade” paintings, such as Mascher Street Façade, 1982 (location unknown), informed by Pop and Graffiti art. He was also represented in The Miami Generation show by etchings, like Basic Colors, 1983 (location unknown), inspired by Renaissance and Baroque art and his interest in theology.

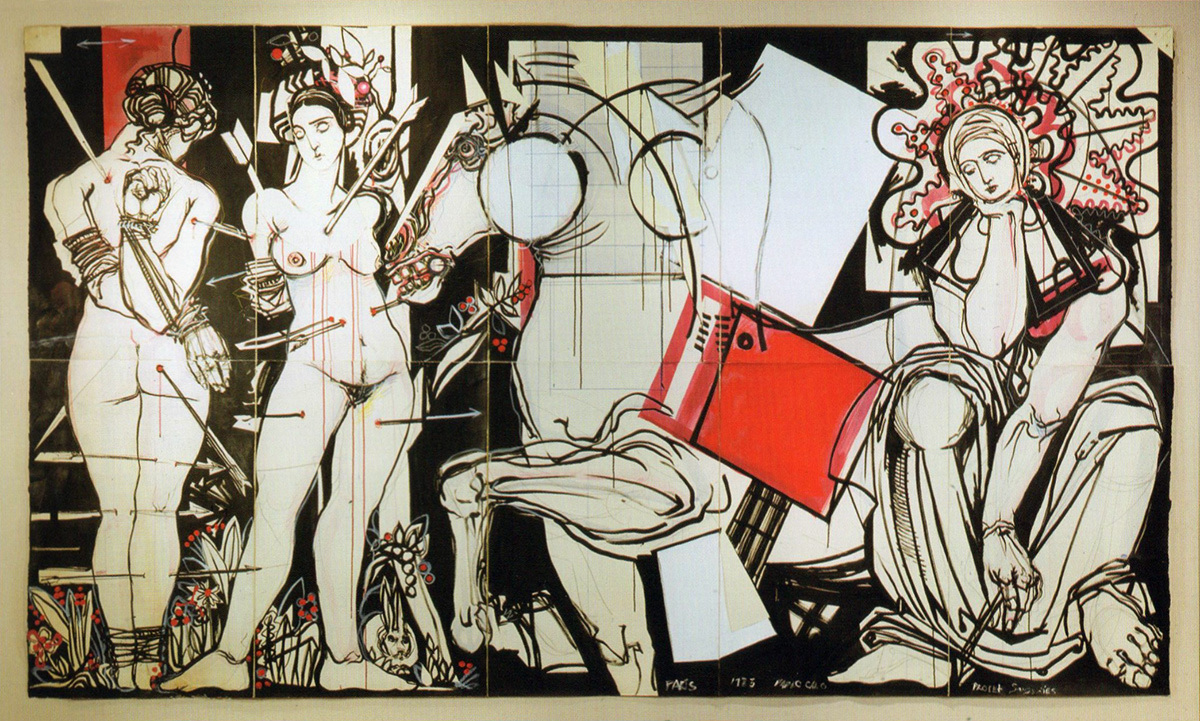

In the early 1980s, Cano was involved with painting, collage, and book making. Cano’s La Sebastiana, 1983 (Collection of John and Lauren Oramas, Miami, Florida), a major early work, included in The Miami Generation exhibition, is a large collage presenting an allegorical and suffering view of Cuba as St. Sebastian(a). As with others in this group, Cano referred at times to his Cuban heritage through Catholic imagery.

As the decade progressed, his work turned to assemblages of found objects, and then to marionettes, as seen in Florabel Marionette Theater, 1985 (Collection of the artist). Since then, his work has doubled as performance pieces and sculpture.

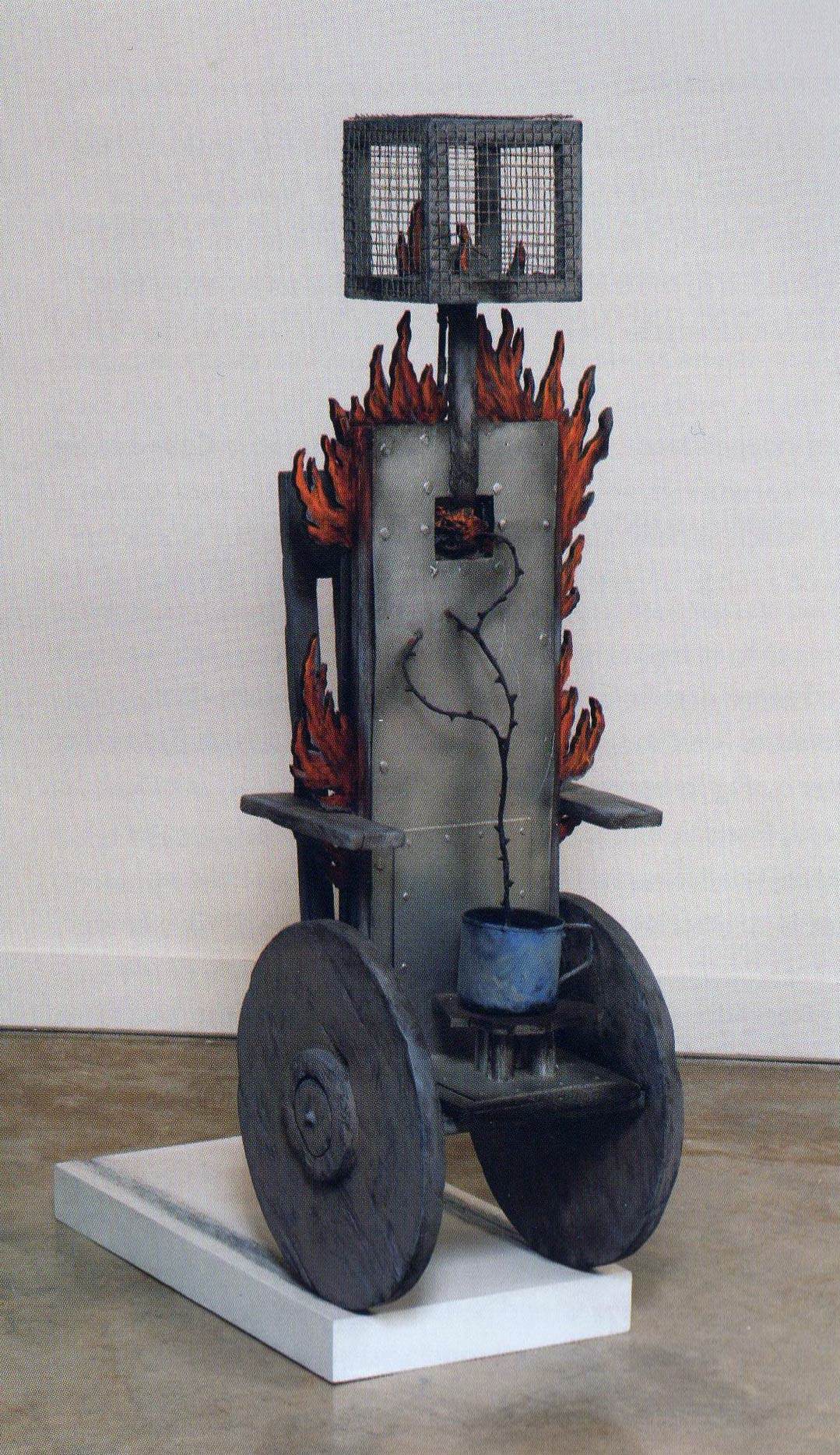

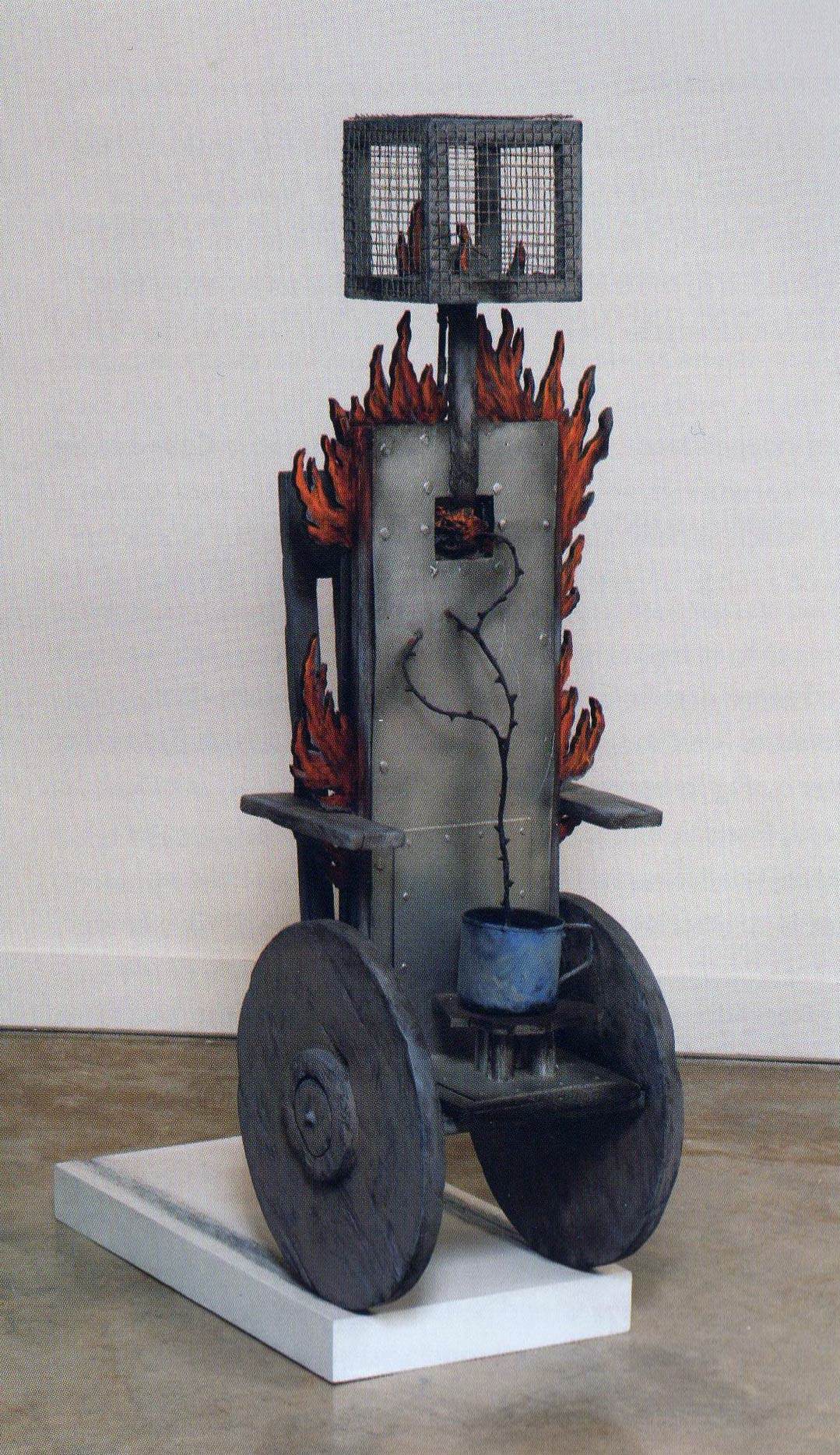

A master of mixed media sculpture, Maria Brito’s inclusion in the exhibition, Woman Before a Mirror, 1983 (Collection of the artist), reclaims a theme going back to Titian (1485-1576), but from a woman’s point of view. She represents woman as subject, rather than object. More tableaux followed in the 1980s with the theme of self-exploration as Cuban-American woman, mother, wife, and human being, as in The Room of the Two Marias, 1984 (Collection of the artist), and Self-Portrait, 1989 (Collection of Arturo and Liza Mosquera, Miami, Florida). The latter is a curious assemblage of a wooden wheelchair, a dry branch, a armor on fire, and a small cage as head. Brito’s symbolic approach to self-portraiture invites questions and projections, but no definite interpretation.

Lastly, García and Trasobares share an interest in conceptual art and engaging with the community. García was represented in the show by one of his most poetic pieces, A Martí 1983 (Private collection, Miami, Florida), which consisted of a mirror with the outline of the Cuban flag etched in it and reflecting a quote from an essay José Martí (1853-1895) wrote on Michelangelo (1475-1564) ,written backwards on the opposite wall.

Martí, the apostle of Cuban independence, has been extensively quoted in Cuba and the Exile community for his political writings, yet García chose to focus on his least known line of writing, art criticism, which fitted perfectly with the site. In his brief, but productive career, García’s work showed a range of concerns from post-minimalism to works engaging Miami’s civic life.

Among his most recognized pieces are Holiday Spheres, 1985 (location unknown), consisting of weather balloons covered in brightly colored symbols and floated over the Miami-Dade Cultural Center during its opening; 10,865, 1980 (Miami-Dade County Public Library, Miami, Florida) a collage using the local media to document the Mariel Boatlift in real time; Anti-Bilingual Bigot, 1987 an ephemeral installation done in collaboration with Carlos Alfonzo (1950-1991), offering biting commentary on Miami’s “language wars” of that decade; and Making Purple, 1988, a neon piece at the Okeechobee Metrorail Station, which is part of the Miami-Dade’s Art in Public Places program.

Trasobares’s exhaustive exploration of the Cuban and Cuban-American popular rite of passage, the Quinceñera, was well represented in The Miami Generation show with pieces such as Les Demoiselles de la Petite Havanne, 1983 (Collection of the artist) and Quinceñera Club Kick Back Officer, 1978 (Perez Art Museum Miami, Florida, Gift of Richard and Ruth Shack). Using collages, boxes, and performances, Trasobares parodied these lavish coming out parties while keeping an anthropologist’s eye on issues of class, aesthetics, and the weight of traditions in the Miami Cuban exile community.

By the late 1980s, these artists had kept a constant presence in South Florida through participation in collective and personal exhibitions from West Palm Beach to Miami, including the Norton Gallery of Art, West Palm Beach, the Museum of Art, Ft. Lauderdale, MOCA, and the Center for the Fine Arts (now the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, Florida). A look at the art reviews of Ellen Edwards and Helen Kohen in The Miami Herald, Rafael Casalins in El Nuevo Herald, Lillian Dobbs and Paula Harper in the now defunct Miami News, and the catalogue essays and magazine articles by Ricardo Pau-Llosa and others reveal that these artists were hot; individually they caught the attention of these and other art critics who wrote from positive to glowing reviews of their art.

The 1980s rise of the concept of multiculturalism and the national interest in the rapidly growing Hispanic (soon to be known as Latino) population projected Miami into the national conversation about the importance of the Hispanic presence in the United States. This new attitude was partly responsible for a number of major traveling exhibitions in which artists of the Miami Generation were well represented. The most relevant exhibition of that decade was Fuera de Cuba/Outside of Cuba, 1987-1989. Organized by Ileana Fuentes Pérez, Graciella Cruz-Taura, and Ricardo Pau- Llosa, the exhibition opened at Rutger’s State University Jane Zimmerli Art Museum, March 22-May 26, 1987 and travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Arts, New York City, June 25-August 2; Miami University Art Museum, Oxford, Ohio, October 16-December 20; Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, July 15-September 8, 1988; Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, Florida, October 5-December 4; and New Visions Gallery of Contemporary Art, Atlanta, Georgia, March 20-April 19, 1989. It included forty-eight artists and had a substantial catalogue.

1980s

Emilio Falero

The Visit

1977

Juan González

Mar de Lágrimas (Sea of Tears)

1987-88

Pablo Cano

La Santa Sebastiana

1983

Maria Brito

Self-Portrait

1989

The Visit

1977

Juan González

Mar de Lágrimas (Sea of Tears)

1987-88

Pablo Cano

La Santa Sebastiana

1983

Maria Brito

Self-Portrait

1989

In the 1990s, Miami grew in leaps and bounds and its population became more diverse. To the east, Downtown Miami doubled the number of its skyscrapers and to the west, new neighborhoods sprung up close to the Everglades. Migration from all countries south of the border continued unabated. All of this growth fueled Miami’s first art “boom.” The art scene became more diffused throughout the city. There was an increase in the number of artists making Miami their home, more galleries opened up, and the collection of art picked up pace. The New World School of the Arts, Miami-Dade College, and Florida International University graduated ever-larger classes of art majors, many of Cuban-American descent and who represent a post Miami Generation.

The Cuban-American population continued to grow mostly due to a new wave of Cubans fleeing an economic depression that the Cuban government called “Special Period in Times of Peace,” but is better known as “el period especial.” In that rather silent and large migration, many of the artists of the renowned 1980s Generation came to live in Miami. In two decades living in the same city, these artists have had little interaction with the Miami generation, except some personal acquaintances. Interestingly, the art of both groups was equally experimental in the early 1980s, as seen in the artworks exhibited 10,085, an exhibition at the Miami-Dade County Main Library in 1980, and those in the renowned Volumen I exhibition at the Havana International Arts Center, Cuba, 1981. Moreover, both generations’ post-1980s artworks, as shown together in three major group exhibitions in the 1990s, are difficult to tell apart. In Havana, as in Miami, these artists were exposed by teachers, art magazines, and travel to the same contemporary artistic trends, mostly coming out of New York. The Miami Generation, however, draws more from art history, particularly modern and pre modern European art, and there are more painters in its ranks.

The decade also took its toll on the Miami Generation in the form of the AIDS epidemic, killing Blanc, Gónzalez and Macía. García died of AIDS at the end of the previous decade.

The 1990s began with an ambitious exhibition of Cuban-American artists, Cuba-USA: The First Generation, 1991-92, curated by Marc Zuver. This exhibition opened in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and traveled to Fondo del Sol Visual Arts Center, Washington, DC; The Minnesota Museum of Art, St. Paul; and The Art Museum at Florida International University, Miami, Florida. The exhibition included forty-four artists living in the United States (a few were deceased) and over one hundred and fifty works in every imaginable medium.

The catalogue includes various essays and artist statements. The decade ended with another large exhibition of Cuban American and Cuban artists: Breaking Barriers 1997, which originated at the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale and traveled to the Tampa Museum of Art, Florida. This exhibition of eighty-eight artists from different generations, mostly living in the United States, included a catalogue with an essay by art historian, Carol Damian, and artist statements.

Jorge Santis, curator, Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art Fort Laderdale, was curator for the exhibition and has facilitated the acquisition by the Museum of one of the most complete collections of contemporary Cuban and Cuban American art in the United States. Two other significant museum collections where the art of the Miami Generation artists is well represented are the University of Miami Lowe Art Museum, which inherited the art collection of the former Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture, and Miami-Dade College, which houses the Oscar B. Cintas art collection. The Miami Generation artists thrived in the 1990s with participation in many group exhibitions and solo shows in the United States, Latin America, and Europe. Their bibliography and recognition expanded during that decade. Locally, new art critics and art historians began to write about them, such as Elisa Turner, who was then writing for The Miami Herald, Armando Alvarez-Bravo, who was writing for El Nuevo Herald, Damian, Cris Hassold, and others writing essays for exhibition catalogues and magazine articles.

Art historian, Lynette M. F. Bosch was curator for a number of exhibitions in the Northeast of Cuban- American artists from Miami, wrote magazine articles on their work, and in 2004 published the only monograph on the art of Cuban Americans, Cuban-American Art in Miami.

The painters Bencomo, Calzada, and Falero stayed the course, honed their craft, and expanded their attention to more universal themes. Bencomo’s abstract paintings became bolder in color, more complex in form, and sensual. His ongoing inspiration in art history, which in the early 1990s led him to Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s (1598-1680) Ecstasy of St. Teresa, 1651 (Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome), motivated a series of paintings on the subject. An outstanding example is Extasis de Santa Teresa, 1993 (Private collection, Doral, Florida).

This large painting suggests the pain and pleasure central to St. Teresa’s ecstasy through the contrast of pointed and rounded, expanding and contracting forms. His interest in literature also motivated important paintings in that decade, such as Lear, Father of Storms, 1995 (Private collection, Doral, Florida).

Calzada’s fascination for Cuban colonial architecture rendered in tight illusionism persisted in the 1990s. The cool nostalgia of his 1980s paintings, with their ordered architectural perspective, emptiness, and distant seascapes gave way to the more universal images of the Flooded Spaces series. As seen in two excellent paintings from this phase, The Collapse of an Island, 1998 the artist) and A Conversation with the Sea, 1998 (Collection of Mr. Edward Guedes and Mr. Ric Ryan, Miami, Florida), flooded buildings suggest the destructive power of the sea, which symbolism ranges from the Biblical to the ruinous state of Havana’s architecture and infrastructure after years of neglect.

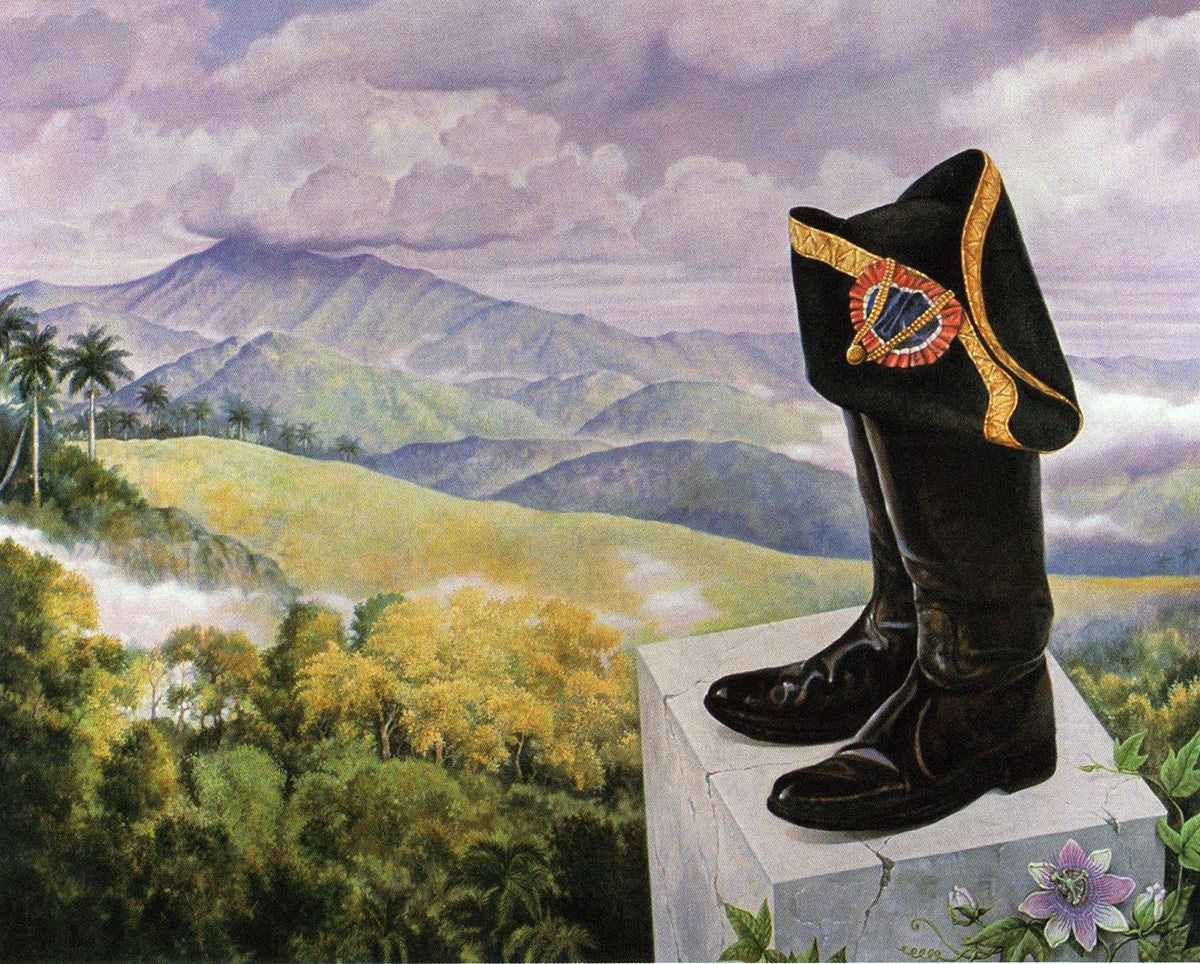

Falero’s realism became more refined and illusionistic in the 1990s as he explored new subject matter based on his Cuban background. One outstanding painting from that period is As We Wait in Joyful Hope 1993 (Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida), which shows Napoleon’s hat and boots on a decaying plinth in the foreground against a view of the Sierra Maestra mountain, famous as Fidel Castro’s base of operation during his insurgency. Inspired by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, the painting is about the transitory nature of tyranny in Cuba and elsewhere.

Two other memorable paintings of that decade are Resurrection 1994 (Collection of Juan Carlos LLera, Miami, Florida), a homage to his friend Juan Gonzalez, and Untitled (Redemptor Hominis), 1994 (NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, Florida). Both are about suffering and redemption and rooted in his deep, Christian, spiritual values and practice. His deliberate, patient manner of working further slowed down his production in the 1990s.

Brito, Cano, and Trasobares kept working with found objects and mixed media constructions and installations. In the 1990s, Brito participated in the Decade Show, 1990 held at The New Museum, New York, The Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, New York, and The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, May 12-August 19, and inclusion in Lucy Lippard’s book Mixed Blessings, 1990.

Both the exhibition and the book promoted a new and more inclusive view of American art. During the 1990s, Brito’s mixed media tableaux and environments increased in size and complexity, such as El Patio de mi casa, 1991 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), Whitewash, 1990 (Collection of the artist),and Merely a Player, 1993 (Collection of the artist). These works, which in the language of dreams and memories allude to home, the roles we play, and life’s journey have a haunting beauty.

Brito also turned her attention to painting, developing a solid body of work on the theme of self-portraiture. In a style and iconography adapted from Renaissance and Baroque paintings, she uses Catholic symbols to explore aspects of her persona and life.

Cano continued to turn garbage into highly imaginative art objects in the 1990s, and his abiding interest in marionettes and the stage reached new heights. During that decade, he introduced performance and music to his mixed media practices, which culminated in the 1997 performance of Animated Altar Pieces and the Pursuit of Love (both, Rubell Family Collection, Miami, Florida) and at MOCA. The former, is about Medieval stories of the saints and the latter, is about the pleasures of love set in the 18th century.

Cano uses stories and characters from the Middle ages and the Rococo periods to explore his own cultural identity. MOCA went on to commission sixteen of his marionette productions, and staged one per year to critical and popular acclaim. His productions are a collaborative effort between the artist, a playwright, a composer, musicians and museum staff.

Trasobares shifted gears in the 1990s from his interest in Cuban -American Miami culture to the politics of the art world and later to a minimal phase. Museum of American Democratic Art: Tumbling Chairs, 1994 (Collection of the artist) exposes the competing forces at work in contemporary art, whereas Gestalt Chairs Studio, 1995 (Collection of Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz and Jill and Janet Eaglstein, Miami, Florida), offer a discreet aesthetic experience.

Towards the end of his brief career, Maciá did drawings and hand crafted mixed media books. Of the latter, Novus Atlas Coelestis, 1992 (Collection of Ruth and Marvin Sackner, Miami, Florida) is a premier example. His last series of drawings are exquisite in technique and rich in symbolism, as seen in Jacob’s Ladder, 1993. In a style inspired by Renaissance art, the drawing depicts six angels hung from a tree, in which the trunk is carved into a ladder, presumably reaching heaven. The drawing is a personal and universal meditation on death and spiritualty, not unlike Gonzlez’s Sea of Tears. Macia’s mature art was strongly influence by his interest and study of theology and philosophy.

The Cuban-American population continued to grow mostly due to a new wave of Cubans fleeing an economic depression that the Cuban government called “Special Period in Times of Peace,” but is better known as “el period especial.” In that rather silent and large migration, many of the artists of the renowned 1980s Generation came to live in Miami. In two decades living in the same city, these artists have had little interaction with the Miami generation, except some personal acquaintances. Interestingly, the art of both groups was equally experimental in the early 1980s, as seen in the artworks exhibited 10,085, an exhibition at the Miami-Dade County Main Library in 1980, and those in the renowned Volumen I exhibition at the Havana International Arts Center, Cuba, 1981. Moreover, both generations’ post-1980s artworks, as shown together in three major group exhibitions in the 1990s, are difficult to tell apart. In Havana, as in Miami, these artists were exposed by teachers, art magazines, and travel to the same contemporary artistic trends, mostly coming out of New York. The Miami Generation, however, draws more from art history, particularly modern and pre modern European art, and there are more painters in its ranks.

The decade also took its toll on the Miami Generation in the form of the AIDS epidemic, killing Blanc, Gónzalez and Macía. García died of AIDS at the end of the previous decade.

The 1990s began with an ambitious exhibition of Cuban-American artists, Cuba-USA: The First Generation, 1991-92, curated by Marc Zuver. This exhibition opened in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and traveled to Fondo del Sol Visual Arts Center, Washington, DC; The Minnesota Museum of Art, St. Paul; and The Art Museum at Florida International University, Miami, Florida. The exhibition included forty-four artists living in the United States (a few were deceased) and over one hundred and fifty works in every imaginable medium.

The catalogue includes various essays and artist statements. The decade ended with another large exhibition of Cuban American and Cuban artists: Breaking Barriers 1997, which originated at the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale and traveled to the Tampa Museum of Art, Florida. This exhibition of eighty-eight artists from different generations, mostly living in the United States, included a catalogue with an essay by art historian, Carol Damian, and artist statements.

Jorge Santis, curator, Nova Southeastern University Museum of Art Fort Laderdale, was curator for the exhibition and has facilitated the acquisition by the Museum of one of the most complete collections of contemporary Cuban and Cuban American art in the United States. Two other significant museum collections where the art of the Miami Generation artists is well represented are the University of Miami Lowe Art Museum, which inherited the art collection of the former Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture, and Miami-Dade College, which houses the Oscar B. Cintas art collection. The Miami Generation artists thrived in the 1990s with participation in many group exhibitions and solo shows in the United States, Latin America, and Europe. Their bibliography and recognition expanded during that decade. Locally, new art critics and art historians began to write about them, such as Elisa Turner, who was then writing for The Miami Herald, Armando Alvarez-Bravo, who was writing for El Nuevo Herald, Damian, Cris Hassold, and others writing essays for exhibition catalogues and magazine articles.

Art historian, Lynette M. F. Bosch was curator for a number of exhibitions in the Northeast of Cuban- American artists from Miami, wrote magazine articles on their work, and in 2004 published the only monograph on the art of Cuban Americans, Cuban-American Art in Miami.

The painters Bencomo, Calzada, and Falero stayed the course, honed their craft, and expanded their attention to more universal themes. Bencomo’s abstract paintings became bolder in color, more complex in form, and sensual. His ongoing inspiration in art history, which in the early 1990s led him to Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s (1598-1680) Ecstasy of St. Teresa, 1651 (Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome), motivated a series of paintings on the subject. An outstanding example is Extasis de Santa Teresa, 1993 (Private collection, Doral, Florida).

This large painting suggests the pain and pleasure central to St. Teresa’s ecstasy through the contrast of pointed and rounded, expanding and contracting forms. His interest in literature also motivated important paintings in that decade, such as Lear, Father of Storms, 1995 (Private collection, Doral, Florida).

Calzada’s fascination for Cuban colonial architecture rendered in tight illusionism persisted in the 1990s. The cool nostalgia of his 1980s paintings, with their ordered architectural perspective, emptiness, and distant seascapes gave way to the more universal images of the Flooded Spaces series. As seen in two excellent paintings from this phase, The Collapse of an Island, 1998 the artist) and A Conversation with the Sea, 1998 (Collection of Mr. Edward Guedes and Mr. Ric Ryan, Miami, Florida), flooded buildings suggest the destructive power of the sea, which symbolism ranges from the Biblical to the ruinous state of Havana’s architecture and infrastructure after years of neglect.

Falero’s realism became more refined and illusionistic in the 1990s as he explored new subject matter based on his Cuban background. One outstanding painting from that period is As We Wait in Joyful Hope 1993 (Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida), which shows Napoleon’s hat and boots on a decaying plinth in the foreground against a view of the Sierra Maestra mountain, famous as Fidel Castro’s base of operation during his insurgency. Inspired by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, the painting is about the transitory nature of tyranny in Cuba and elsewhere.

Two other memorable paintings of that decade are Resurrection 1994 (Collection of Juan Carlos LLera, Miami, Florida), a homage to his friend Juan Gonzalez, and Untitled (Redemptor Hominis), 1994 (NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, Florida). Both are about suffering and redemption and rooted in his deep, Christian, spiritual values and practice. His deliberate, patient manner of working further slowed down his production in the 1990s.

Brito, Cano, and Trasobares kept working with found objects and mixed media constructions and installations. In the 1990s, Brito participated in the Decade Show, 1990 held at The New Museum, New York, The Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, New York, and The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, May 12-August 19, and inclusion in Lucy Lippard’s book Mixed Blessings, 1990.

Both the exhibition and the book promoted a new and more inclusive view of American art. During the 1990s, Brito’s mixed media tableaux and environments increased in size and complexity, such as El Patio de mi casa, 1991 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC), Whitewash, 1990 (Collection of the artist),and Merely a Player, 1993 (Collection of the artist). These works, which in the language of dreams and memories allude to home, the roles we play, and life’s journey have a haunting beauty.

Brito also turned her attention to painting, developing a solid body of work on the theme of self-portraiture. In a style and iconography adapted from Renaissance and Baroque paintings, she uses Catholic symbols to explore aspects of her persona and life.

Cano continued to turn garbage into highly imaginative art objects in the 1990s, and his abiding interest in marionettes and the stage reached new heights. During that decade, he introduced performance and music to his mixed media practices, which culminated in the 1997 performance of Animated Altar Pieces and the Pursuit of Love (both, Rubell Family Collection, Miami, Florida) and at MOCA. The former, is about Medieval stories of the saints and the latter, is about the pleasures of love set in the 18th century.

Cano uses stories and characters from the Middle ages and the Rococo periods to explore his own cultural identity. MOCA went on to commission sixteen of his marionette productions, and staged one per year to critical and popular acclaim. His productions are a collaborative effort between the artist, a playwright, a composer, musicians and museum staff.

Trasobares shifted gears in the 1990s from his interest in Cuban -American Miami culture to the politics of the art world and later to a minimal phase. Museum of American Democratic Art: Tumbling Chairs, 1994 (Collection of the artist) exposes the competing forces at work in contemporary art, whereas Gestalt Chairs Studio, 1995 (Collection of Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz and Jill and Janet Eaglstein, Miami, Florida), offer a discreet aesthetic experience.

Towards the end of his brief career, Maciá did drawings and hand crafted mixed media books. Of the latter, Novus Atlas Coelestis, 1992 (Collection of Ruth and Marvin Sackner, Miami, Florida) is a premier example. His last series of drawings are exquisite in technique and rich in symbolism, as seen in Jacob’s Ladder, 1993. In a style inspired by Renaissance art, the drawing depicts six angels hung from a tree, in which the trunk is carved into a ladder, presumably reaching heaven. The drawing is a personal and universal meditation on death and spiritualty, not unlike Gonzlez’s Sea of Tears. Macia’s mature art was strongly influence by his interest and study of theology and philosophy.

1990s

Mario Bencomo

Extasis de Santa Teresa

1993

Humberto Calzada

The Collapse of an Island

1998

The big art event of the new millennia in Miami was the arrival of Art Basel. It made the city a contemporary art market destination, supported by satellite art fairs and a mushrooming of galleries, most visible in Wynwood. Accompanying the growth in the art market for contemporary art, a number of museums and large private collections with their own facilities offered a wealth of contemporary art exhibitions and educational programs.

As the art scene in Miami expanded exponentially in size and diversity, art coverage in the local media did not. Only three newspapers, The Miami Herald, El Nuevo Herald and the Miami New Times print regular exhibition reviews. Recently bloggers have picked up the slack. In the new globalized Miami art market, far from the heyday of multiculturalism and identity politics of the 1980s, the Miami Generation as a group has been largely forgotten. Two exceptions are Bosch’s aforementioned book, and this exhibition, The Miami Generation: Revisited.

Its artists are successful thirty years into their artistic career as measured by awards, solo shows in galleries and museums, participation in national and international exhibitions organized around diverse themes, and representation in numerous public and private collections.

They have also enjoyed critical attention, with ever more art historians, curators, and critics writing about their work. In the last decade, aside from the aforementioned writers, Joel Weinstein, Alfredo Thriff, Alejandro Anreus, Elizabeth Cerejido, and Janet Batet, have written eloquent reviews and catalogue essays of individual artists from this generation.

The journey has not been easy. On the local level, there has been little institutional support and modest private collecting, even though there is a sizable wealthy class of Cuban-Americans in Miami from their own generation. More difficult still, has been representation on the national and international stage for any artists coming from an ethnic minority and living in a peripheral city. Furthermore, the high international interest in contemporary Cuban art from the island has overshadowed the art of Cuban-Americans living in Miami, which is perceived to be less “authentic” and on the wrong side of history.

The artists in The Miami Generation exhibition continued to evolve in the new millennia. Brito introduced the human figure into her mixed media tableaux and environments and took on social commentary on human follies, as seen in Crop, 2004, Of Mice and Man, 2005, and the monumental As of 24-03-07, 2007 (all, Collection of the artist). Brito’s contribution to contemporary art is evoking an intense psychological state of mind or biting social commentary in her work. Cano has steadily developed more complex marionettes and performances. His introduction of dance in the last decade has led to more agile marionettes, as seen in Queen Marie Antoinette (Collection of the artist), from the performance Viva Vaudeville 2007 at MOCA. He also continues to make freestanding sculpture, like Lady Electra, 2013 (Collection of the artist).

Cano has brought the tradition of Dada and Russian avant-garde theater up-to-date, imbuing it with his own sense of humor and the absurd, as well as his cultural identity. Trasobares continues to mix art making, mostly installations, with art education and curatorship. He is a skillful wordsmith with a keen sense of satire and an eye for pop culture. Two outstanding works of the last decade are Social Fabric: Old Pillows and Recent Money Works, 2003 (Collection of the artist), and Conservatorium, 2005 (Collection of the artist). The latter, shown at the Wolfsonian-Florida International University Museum in Miami Beach during Art Basel, 2006, offered a large installation of his life long interest in reconstituting money bills and making and collecting rings. The complex piece explores, among other themes, the fascination with cash and consumption in a capitalist society. Trasobares’ work represents a significant contribution to conceptual art with a critical social edge.

The painters of this generation pushed ahead with their craft in what amounts to an act of resistance, given the contemporary art world’s hostility to such a medium. Bencomo’s color poems deepened the painting’s spiritual resonance and visual pleasure. A master in the exploration of ambiguous and alluring organic forms, his abstractions gained in density as seen in Cocuyos (Location unknown), or Esther’s Journey (Collection of the artist) from the 2003 exhibition Wanderlust at Elite Fine Art in Coral Gables, Florida, or became more contained as in Metamorphosis (Collection of Mercy and Juan Esterripa, Miami, Florida) or Medusiana (Collection of Carlos Serradet, Miami, Florida) from the 2010 exhibition Utopia: If Québec were in the Tropics at Beaux-arts des Amériques, Montréal, Canada.

Most recently, Bencomo has done a series of works with a striking use of black and is based on Federico García Lorca’s (1898-1936) poem Poet in New York. The piece, Ode To Whitman, 2013 (Collection of Ana M. Bermudez, Coconut Grove, Florida), is a prime example. Bencomo’s contribution to the tradition of modernist abstraction lies in his evocation of nature in the tropics as a dreamed and desired mental space.

Since 2000, Calzada has developed new painting series in his signature style of meticulous, still, architectural visions, culminating in a retrospective exhibition at the Lowe Art Museum in 2006. He expanded his 1990s tribute to other painters with new homages, such as Edward Hopper in Cuba, 2004 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. William Thompson, Miami, Florida), with whom he shares an interest in the representation of buildings, clear light, and quiet compositions. In the last few years, Calzada has stepped into new territory with his series Reconstructing Havana, 2009-10 and The Fire Next Time exhibition of 2011 at The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida International University, Miami Florida.

In the former series, he paints over color photographs of dilapidated buildings in Havana, starkly juxtaposing their ruinous state with parts that he has painted to look repaired. These paintings look towards the past and the future simultaneously. The latter series represents a radical shift in his work. Using an expressionistic visual language that at times borders on abstraction, he explored new subjects like communication towers, an airport, cities, and landscapes enveloped in fire. Two outstanding examples are Presencing, 2011 (Collection of Mr. Bruce Loshusan, Miami, Florida), and Last Call, 2011 (Perez Art Museum, Miami, Florida). More than the Flood paintings of the 1990s, these have an apocalyptic quality and a totally new emotional tenor. Calzada’s paintings have made a unique contribution to the universal theme of the ancestral home.

Falero’s methodical approach, finishing no more than four paintings per year persists, so does his detailed (sur) realism. In mid-2000 paintings, such as La maja y el tomeguín, 2006 (Collection of the artist), he began to juxtapose appropriated European pre-modern art with the Cuban landscape. The figures range from Goya’s majas to the Virgin and Christ seen against a palm dotted landscape, the sea, or Havana’s Morro Castle. Falero’s interest in a Cuban setting for European figures/traditions jibes well with the predominantly white, Catholic Cuban American culture of the historic exile. Falero is an early practitioner of post-modernism in South Florida, a master of appropriation, juxtaposition, and art about art.

As the art scene in Miami expanded exponentially in size and diversity, art coverage in the local media did not. Only three newspapers, The Miami Herald, El Nuevo Herald and the Miami New Times print regular exhibition reviews. Recently bloggers have picked up the slack. In the new globalized Miami art market, far from the heyday of multiculturalism and identity politics of the 1980s, the Miami Generation as a group has been largely forgotten. Two exceptions are Bosch’s aforementioned book, and this exhibition, The Miami Generation: Revisited.

Its artists are successful thirty years into their artistic career as measured by awards, solo shows in galleries and museums, participation in national and international exhibitions organized around diverse themes, and representation in numerous public and private collections.

They have also enjoyed critical attention, with ever more art historians, curators, and critics writing about their work. In the last decade, aside from the aforementioned writers, Joel Weinstein, Alfredo Thriff, Alejandro Anreus, Elizabeth Cerejido, and Janet Batet, have written eloquent reviews and catalogue essays of individual artists from this generation.

The journey has not been easy. On the local level, there has been little institutional support and modest private collecting, even though there is a sizable wealthy class of Cuban-Americans in Miami from their own generation. More difficult still, has been representation on the national and international stage for any artists coming from an ethnic minority and living in a peripheral city. Furthermore, the high international interest in contemporary Cuban art from the island has overshadowed the art of Cuban-Americans living in Miami, which is perceived to be less “authentic” and on the wrong side of history.

The artists in The Miami Generation exhibition continued to evolve in the new millennia. Brito introduced the human figure into her mixed media tableaux and environments and took on social commentary on human follies, as seen in Crop, 2004, Of Mice and Man, 2005, and the monumental As of 24-03-07, 2007 (all, Collection of the artist). Brito’s contribution to contemporary art is evoking an intense psychological state of mind or biting social commentary in her work. Cano has steadily developed more complex marionettes and performances. His introduction of dance in the last decade has led to more agile marionettes, as seen in Queen Marie Antoinette (Collection of the artist), from the performance Viva Vaudeville 2007 at MOCA. He also continues to make freestanding sculpture, like Lady Electra, 2013 (Collection of the artist).

Cano has brought the tradition of Dada and Russian avant-garde theater up-to-date, imbuing it with his own sense of humor and the absurd, as well as his cultural identity. Trasobares continues to mix art making, mostly installations, with art education and curatorship. He is a skillful wordsmith with a keen sense of satire and an eye for pop culture. Two outstanding works of the last decade are Social Fabric: Old Pillows and Recent Money Works, 2003 (Collection of the artist), and Conservatorium, 2005 (Collection of the artist). The latter, shown at the Wolfsonian-Florida International University Museum in Miami Beach during Art Basel, 2006, offered a large installation of his life long interest in reconstituting money bills and making and collecting rings. The complex piece explores, among other themes, the fascination with cash and consumption in a capitalist society. Trasobares’ work represents a significant contribution to conceptual art with a critical social edge.

The painters of this generation pushed ahead with their craft in what amounts to an act of resistance, given the contemporary art world’s hostility to such a medium. Bencomo’s color poems deepened the painting’s spiritual resonance and visual pleasure. A master in the exploration of ambiguous and alluring organic forms, his abstractions gained in density as seen in Cocuyos (Location unknown), or Esther’s Journey (Collection of the artist) from the 2003 exhibition Wanderlust at Elite Fine Art in Coral Gables, Florida, or became more contained as in Metamorphosis (Collection of Mercy and Juan Esterripa, Miami, Florida) or Medusiana (Collection of Carlos Serradet, Miami, Florida) from the 2010 exhibition Utopia: If Québec were in the Tropics at Beaux-arts des Amériques, Montréal, Canada.

Most recently, Bencomo has done a series of works with a striking use of black and is based on Federico García Lorca’s (1898-1936) poem Poet in New York. The piece, Ode To Whitman, 2013 (Collection of Ana M. Bermudez, Coconut Grove, Florida), is a prime example. Bencomo’s contribution to the tradition of modernist abstraction lies in his evocation of nature in the tropics as a dreamed and desired mental space.

Since 2000, Calzada has developed new painting series in his signature style of meticulous, still, architectural visions, culminating in a retrospective exhibition at the Lowe Art Museum in 2006. He expanded his 1990s tribute to other painters with new homages, such as Edward Hopper in Cuba, 2004 (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. William Thompson, Miami, Florida), with whom he shares an interest in the representation of buildings, clear light, and quiet compositions. In the last few years, Calzada has stepped into new territory with his series Reconstructing Havana, 2009-10 and The Fire Next Time exhibition of 2011 at The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida International University, Miami Florida.

In the former series, he paints over color photographs of dilapidated buildings in Havana, starkly juxtaposing their ruinous state with parts that he has painted to look repaired. These paintings look towards the past and the future simultaneously. The latter series represents a radical shift in his work. Using an expressionistic visual language that at times borders on abstraction, he explored new subjects like communication towers, an airport, cities, and landscapes enveloped in fire. Two outstanding examples are Presencing, 2011 (Collection of Mr. Bruce Loshusan, Miami, Florida), and Last Call, 2011 (Perez Art Museum, Miami, Florida). More than the Flood paintings of the 1990s, these have an apocalyptic quality and a totally new emotional tenor. Calzada’s paintings have made a unique contribution to the universal theme of the ancestral home.

Falero’s methodical approach, finishing no more than four paintings per year persists, so does his detailed (sur) realism. In mid-2000 paintings, such as La maja y el tomeguín, 2006 (Collection of the artist), he began to juxtapose appropriated European pre-modern art with the Cuban landscape. The figures range from Goya’s majas to the Virgin and Christ seen against a palm dotted landscape, the sea, or Havana’s Morro Castle. Falero’s interest in a Cuban setting for European figures/traditions jibes well with the predominantly white, Catholic Cuban American culture of the historic exile. Falero is an early practitioner of post-modernism in South Florida, a master of appropriation, juxtaposition, and art about art.

2000’s

Cesar Trasobares

Queen Marie Antoinette

Mario Bencomo, Ode to Whitman

Homage to Lorca, Poet in New York

2013

Humberto Calzada

Presencing

2011

To paraphrase McCabe’s statement of thirty years ago, it has been interesting for me to watch these Cuban-American artists flourish, as they have become known nationally. What is more elusive is the expectation that their art, as she put it: “[will] retain the special bicultural qualities which permeate this [the 1983] exhibition.” Then and now what is Cuban-American about their art is usually more implicit than explicit. One may have expected that first generation of exiles living in the epicenter of a highly vocal exile community would have produced a sizable amount of political art, but that is not the case.

While some have made memorable works of art that refer to Cuban socio-political themes, these are few and far between. Nevertheless, García’s 10,865, 1980 (Miami-Dade County Public Library), Brito’s Pero sin amo, 2000 (Collection of the artist), and Trasobares’ e-niño, 1996-2000 (The Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida) offer strong statements on Cuban migration in the last thirty some years. Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope, 1993 (The Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami), and Cano’s Once Upon an Island, 2000 (Collection of the artist), address the subject of dictatorship. Brito, Calzada, González, and Falero have presented the exile themes of dislocation and memory in their work.

Cultural traditions, like Catholicism, have influenced the art of González, Maciá, Falero, Brito, Cano, and Bencomo. On this subject, Lynette Bosch wrote: “By mining the symbolic imagery of Renaissance and Baroque art these artists have recontextualized the original meaning of these Italian and Spanish artists into a vehicle for conveying their thoughts about heir identity and their experience.”

Images of paradise lost, suffering, ecstasy, and redemption served to express their exile-immigrant experiences. In some cases the European Catholic mind-set worked at a deeper level than iconography. As González put it: The organization, presentation and sense of ritual in my work draws from my Cuban-Catholic background. My American experience has provided me with a cultural and historical overview.” This generation, as with most Cuban exiles of the 1960s, were of Spanish and Catholic descent, and this heritage runs deep in terms of their cultural identity vis-à-vis American Protestantism, Cuban communism, and Afro-Cuban culture.

Another generational characteristic is the broad “cultural and historical overview” that an American education provided. Taking advantage of globalization, technology, and travel as well as the permissiveness of post-modernism, these artists drew primarily from American and European artistic sources rather than Cuban and Latin American art. Each artist has freely incorporated the ideas, styles and/or techniques of international contemporary art to develop highly personal, content driven, and well crafted works of art.

García may have spoken for his generation when he said, “I feel equally as comfortable in all situations, American or Cuban. Some of my personal habits have been shaped by my Cuban upbringing. In my work, though, I have at times incorporated Cuban themes, but in most instances however I deal with more universal themes.”

All of these artists have at one point or another dealt with Cuban-American themes, but more often than not, the aim has been to create art without a hyphen. As Blanc succinctly and poetically concluded in his Miami Generation catalogue essay, “They are Cuban, they are American, and they are something more.”

While some have made memorable works of art that refer to Cuban socio-political themes, these are few and far between. Nevertheless, García’s 10,865, 1980 (Miami-Dade County Public Library), Brito’s Pero sin amo, 2000 (Collection of the artist), and Trasobares’ e-niño, 1996-2000 (The Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida) offer strong statements on Cuban migration in the last thirty some years. Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope, 1993 (The Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami), and Cano’s Once Upon an Island, 2000 (Collection of the artist), address the subject of dictatorship. Brito, Calzada, González, and Falero have presented the exile themes of dislocation and memory in their work.

Cultural traditions, like Catholicism, have influenced the art of González, Maciá, Falero, Brito, Cano, and Bencomo. On this subject, Lynette Bosch wrote: “By mining the symbolic imagery of Renaissance and Baroque art these artists have recontextualized the original meaning of these Italian and Spanish artists into a vehicle for conveying their thoughts about heir identity and their experience.”

Images of paradise lost, suffering, ecstasy, and redemption served to express their exile-immigrant experiences. In some cases the European Catholic mind-set worked at a deeper level than iconography. As González put it: The organization, presentation and sense of ritual in my work draws from my Cuban-Catholic background. My American experience has provided me with a cultural and historical overview.” This generation, as with most Cuban exiles of the 1960s, were of Spanish and Catholic descent, and this heritage runs deep in terms of their cultural identity vis-à-vis American Protestantism, Cuban communism, and Afro-Cuban culture.

Another generational characteristic is the broad “cultural and historical overview” that an American education provided. Taking advantage of globalization, technology, and travel as well as the permissiveness of post-modernism, these artists drew primarily from American and European artistic sources rather than Cuban and Latin American art. Each artist has freely incorporated the ideas, styles and/or techniques of international contemporary art to develop highly personal, content driven, and well crafted works of art.

García may have spoken for his generation when he said, “I feel equally as comfortable in all situations, American or Cuban. Some of my personal habits have been shaped by my Cuban upbringing. In my work, though, I have at times incorporated Cuban themes, but in most instances however I deal with more universal themes.”

All of these artists have at one point or another dealt with Cuban-American themes, but more often than not, the aim has been to create art without a hyphen. As Blanc succinctly and poetically concluded in his Miami Generation catalogue essay, “They are Cuban, they are American, and they are something more.”

Concluding

Remarks

Emilio Falero

As We Wait in Joyful Hope

1993

César Trasobares

Conservatorium

2005

As We Wait in Joyful Hope

1993

César Trasobares

Conservatorium

2005