Juan A Martinez, 2018

Due to limited space, curatorial choice, and unsolicited gifts, the larger part of museums’ collections are hardly or never seen. For all of those reasons, the Cuban and Cuban American collection of art at the Lowe Art Museum of the University of Miami is little known. Nevertheless, it is a large collection of 586 artworks, dating from about 1920 to 2000, and includes art from well-known artists to a few amateurs. If you are interested, here is some general information about the collection and an imaginary exhibition aiming to make my favorite parts of its holdings better known.

In the mid 1990s, the defunct Cuban Museum of Art and Culture became the Cuban Museum of the Americas. Yes, a strange name. It’s last director, Ileana Fuentes, asked a good number of artists of the Miami Generation, those associated with the Mariel Boatlift of 1980, and artists of Havana’s 1980s Generation then living in Miami, to donate one of their artworks to the museum. Most of the artists heeded the call and gifted good to excellent pieces. She then held a rare and beautiful exhibition of these three groups of artists, which to the best of my knowledge, had never been seen together. Unfortunately, it did not have a catalogue, which today could testify to the vibrant scene of art done by Cubans and Cuban Americans in Miami of the 1980s and 1990s. By Cuban Americans, I mean those artists formed in the United States. The contribution of these discrete groups of artists to the Miami art world has hardly being documented and never assessed. When the Cuban museum folded a few years later, it’s entire collection was given to the Lowe Art Museum. At the same time, it’s archives passed to the Cuban Heritage Collection of the Richter Library at the University of Miami, which makes the Lowe a natural repository for the art.

In 1999, soon after the Lowe Art Museum acquired the collection, it’s then director Brian Dursum asked me to curate a show based on those holdings. The result was an exhibition entitled From Modern to Contemporary Cuban Art (2000). It had to be curated in a hurry to showcase the museum’s new acquisition and it was done without a budget, thus no catalogue.

The show included a fraction of the collection given to the Lowe, and drew from four outstanding multi-works donations given to the Cuban Museum during its brief existence. I like to think of them as collections within the collection. There are the works secured by Iliana Fuentes, mentioned above. The collection of Wifredo Lam’s drawings and rare portrait paintings donated by the Cuban ethnographer Lydia Cabrera. She was a close friend of the artist in the 1940s. An aside, there are enough works on paper by Lam in the Lowe’s entire collection to curate a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of this artist. Then, there is the small, but historically significant collection given by the Nicaraguan journalist Eduardo Aviles Ramirez. While living in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, Aviles Ramirez befriended and helped many visiting Cuban artists, gathering an intimate collection of modern Cuban art at its inception. A much larger donation is the former collection of Rafael Casalins, the food critic for El Nuevo Herald in the 1980s. This is a wide ranging collection of Cuban modern and contemporary art, including eight 1950s paintings by the group Los Once, rare in Miami until the recent interest in Cuban abstract art. To be sure, the Lowe Art Museum’s collection of Cuban and Cuban American art is more extensive than the holding sources mentioned above. It is the largest in any museum in Dade County.

I have a modest proposal for the Lowe: dedicate one sizable room for a month or six weeks every year to showcase different parts of the Cuban and Cuban American art collection. I will begin with an imaginary show of what I consider salient pieces by the Miami Generation. This name is given to a generation of Cuban American artists, who came to Miami as adolescents, grew up in this city, and have been working here as artists for the last forty years. It is a very loose group of artists, some have MFA degrees, others a BA or AA, and a few are self-taught. For more information about many of these artists, please see the catalogue: The Miami Generation Revisited, The Art Museum, Ft. Lauderdale, 2013 (Please see one of the articles in that catalog in this website.)

My imaginary exhibition, besides my personal taste, aims to suggest the variety of themes, media, and quality (that problematic, but I believe still subjectively valid word) of works produced by the artists of that generation. Giving my primary interest in making the works visible, I make no attempt to come up with an overarching theme or theory regarding the art of Cuban Americans. I will leave that for another time, or even better, another curator. My curatorial choice includes: Maria Brito’s The Room Upstairs: Self-Portrait with Two Friends 1984; Mario Bencomo’s Requiem, 1993; Pablo Cano’s Princess Havana 1999; Humberto Calzada’s Still Life in Barragan’s Scenography 1987; Emilio Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope 1993; Maria Martínez Cañas’ Big City Love II, 1986-1987; Arturo Rodríguez’s On the Floor of the Sky III, 1994; and Cesar Trasobares’s E-Nino, 1996-2000.

On entering the space you would be greeted by Cano’s Princess Havana. Cano is a mixed media sculptor, painter, and puppeteer, who emerged as an artist around 1980. The humorous assemblage in question is a rod puppet, which depicts a royal lady, made of the most unlikely materials. She stands in front of a microphone and has the floor. The piece can be seen as a symbol of Havana, given its emblematic quality. It can also be interpreted as a light melancholic representation of the Cuban high class who went into exile. I will bypass the most obvious reading of her being an entertainer, given the microphone. (For a full discussion of this piece, please see Cano’s Royal Ladies).

On the opposite end of the room, I would place Cesar Trasobares’ installation E-Nino. Trasobares is a conceptual artist and activist, who emerged as an artist in the late 1970s. E Nino is a map of the island of Cuba painted on the wall, with works on paper place around it. Originally, when shown at the Cuban museum, it had a different title, which alluded to the exhibition and was event specific: A Gift with Cuban Motif. At the Lowe, the map was painted grey and the names of the Cuban cities and towns were substituted with the name of foreign cities. This displacement of names aptly suggest the Cuban exodus, it’s goings and comings. Geography becomes relative and borders expand. The works on paper above and below the map are mostly personal and relate to periods in his long trajectory. Some relate to his interest in furniture, others to his investigation of the Quinceñera coming of age parties, a couple are of childhood photos with superimposed writings, and a few are grocery advertisements. These last ones reveal Trasobares as an artist-anthropologist of Miami Cuban popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s. One of the early successful business ventures of Cuban exiles in Miami was owning neighborhood grocery stores. Here Cubans could buy the products used in their cuisine, a lifeline to keeping tradition alive and their stomach satisfied. Once or twice a week, the store owner printed on 8 x 10 white paper the specials of the week, and delivered the ads to neighborhood homes, placing them in the mailbox or the door. Trasobares appropriated these crude advertisements and placed them in art exhibitions, not for their aesthetic design, but for their mundane yet significant social/cultural value. This entire installation does not speak about yesterday Cuba, but about what it’s exiles and immigrants took with them to their new place: a strong sense of identity, nostalgic memories, and in lots of cases, the know how to forge ahead.

On the walls between the two mentioned artworks, I would place the two-dimensional and relief pieces. Mario Bencomo is an abstract painter, who mostly works on canvas and large

paper format. He emerged as an artist in the early 1980s. One of my favorite pieces by him is in the Lowe collection, titled Requiem. This is a small mixed media on wood, which rich surface is painted in purple with a loose triangular area of vibrant red at the center. This center is accentuated by a three-dimensional ring, the one defined shape in the composition. Bencomo often works in series and this one belongs to the Torquemada Series. Tomás de Torquemada was a Castilian Dominican friar, and the first Grand Inquisitor in Spain's movement to homogenize religious practices with those of the Catholic Church. He lived in the late 15th century. Bencomo’s painting is a requiem for all of the victims of that phase of the Spanish Inquisition. It is a meditative image with a strong, somber mood. It’s emotional impact is much greater than its size.

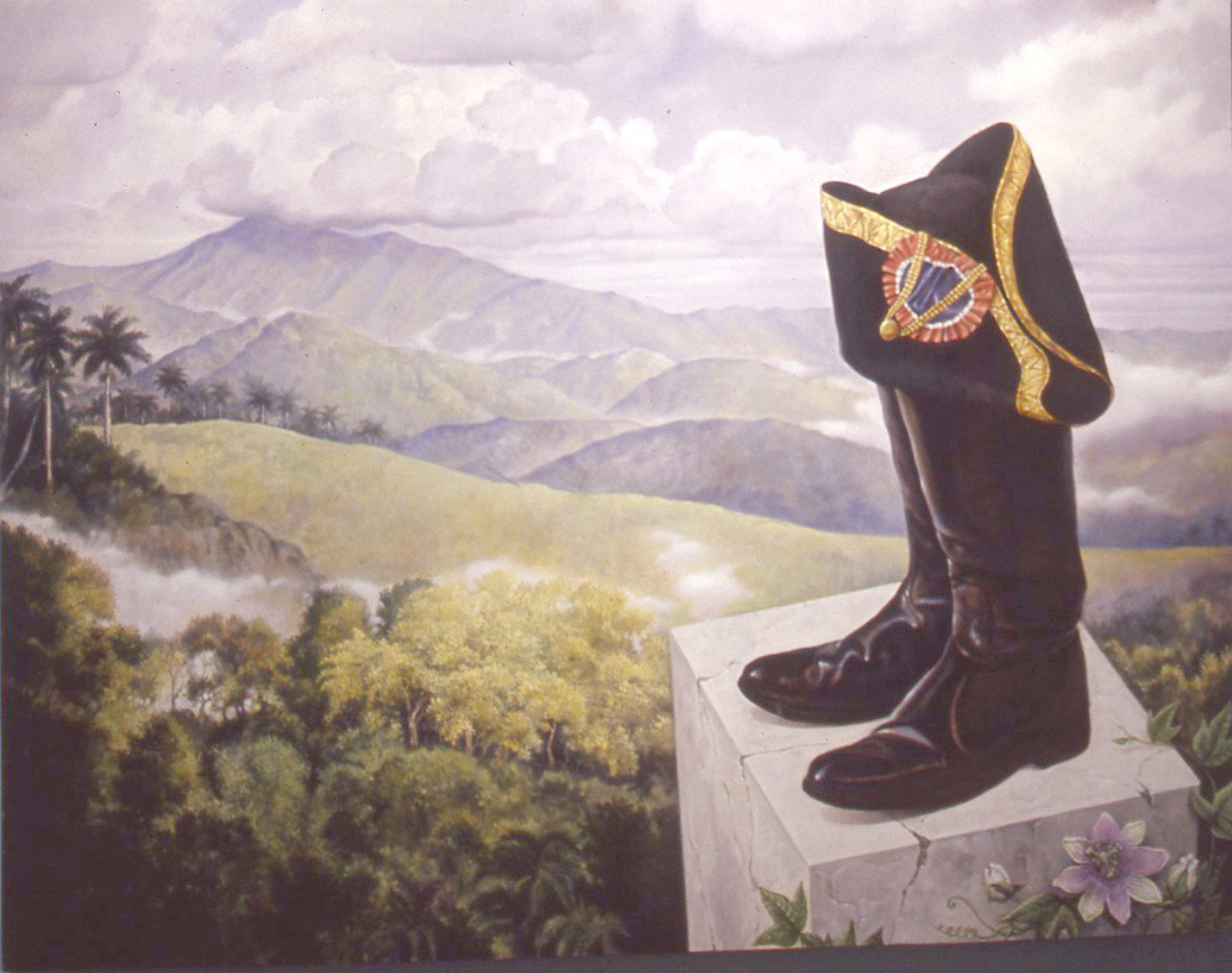

Next, I would place another painting, which also obliquely references the Catholic mass. Emilio Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope is painted in his tight realistic style, yet differs in subject matter from most of his work. Falero is a figurative painter, who emerged as an artist in the mid-1970s, and was influenced by the New Realism movement of that time. The Lowe Art Museum’s anonymous quote in its website offers an excellent introduction to this painting. “(It) is an allegory of world domination and the historical transience of political power. A lush Cuban landscape stretches eternally beyond a crumbling column encroached upon by a vine and flower, on top of which sits Napoleon’s tri-corner hat and boots. The artist implies that nature, enduring, will never succumb to man, no matter how enormous and mighty the human aggression, nor can corruption survive. While Napoleon was never a part of the political history of Cuba, for Falero, he symbolizes and represents the inevitable end of oppression and oppressor. Given Cuba’s recent political history, the painting also operates on another more literal level of interpretation, expressed through the title, which comes from a prayer said during Catholic mass.”

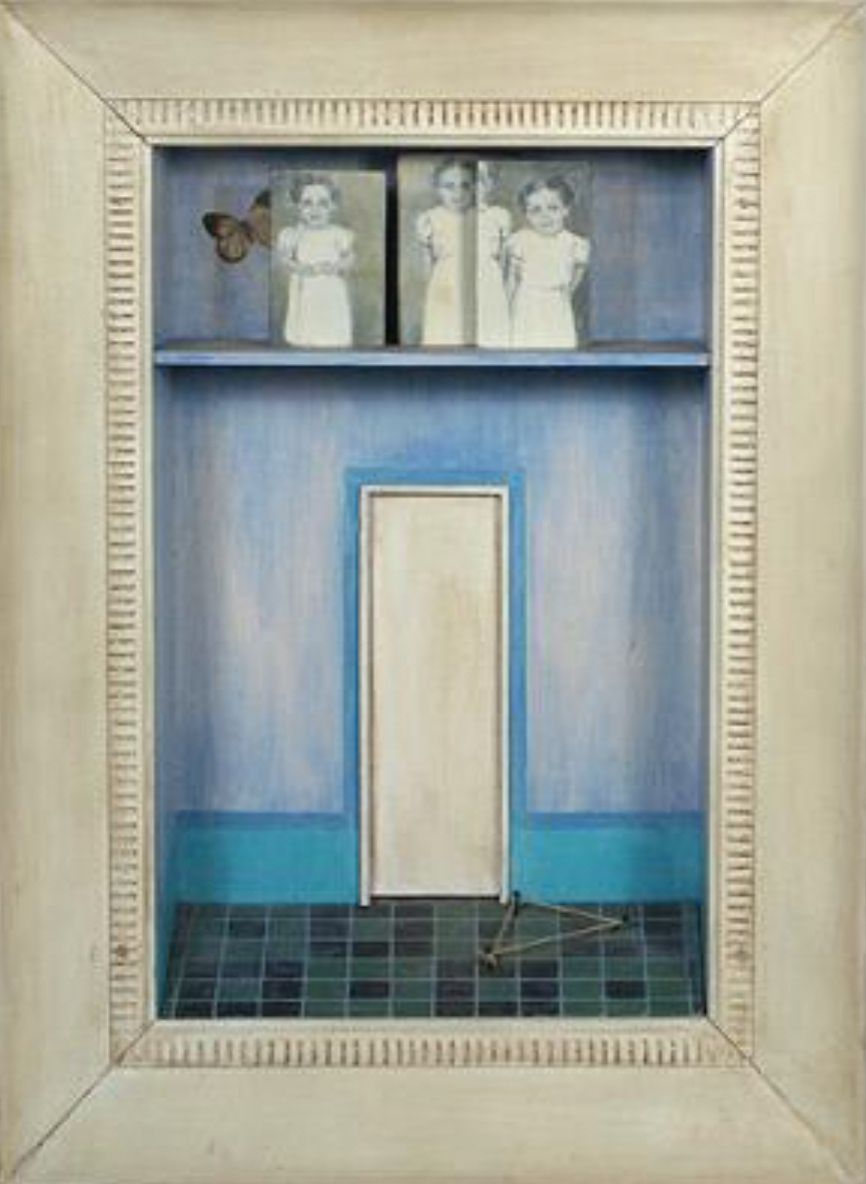

Maria Brito is a mixed media sculptor, painter, and professor, who emerged as an artist around 1980. Next, I would hang Brito’s personal and poetic The Room Upstairs: Self-Portrait with Two Friends. This intimate assemblage is a shallow box. It’s lower part represents an empty interior with tile floor, blue walls, and a white closed door in the center; the upper part of the composition, a second floor, depicts three similar looking girls dressed in white. The one to the left has a fully colored butterfly next to her shoulder and the center figure is divided down the middle of her body. The first floor suggests quietness and solitude, the second floor, fantasy and freedom. The similarity of the girls and the splitting of one of the girl’s body make me think of imaginary friends, while the butterfly conjures thoughts of liberty and transformation. This mesmerizing piece has the quality of a dream or a memory. Brito dove deep into her past to better know herself, and in the end, give us all an insight into childhood and recollection.

I would continue with the theme of memory, if of a different nature and means of expressing it: Humberto Calzada’s Still Life in Barragan’s Scenography. Calzada is a realist painter and printmaker, who emerged as an artist in the mid 1970s. This painting is from the second phase of his long exploration of Cuban Colonial architecture as a symbol of homestead. Craftsmen from southern Spain and their Cuban born descendants created a more or less unique architecture in the19th century for the island’s white elite. In the 1940s, when this architecture was deteriorating, a generation of architects, artists, and intellectuals foregrounded it as a sign of that which is Cuban, especially in relation to its Spanish heritage, which they argued was the dominant side of the Cuban identity. In exile, Calzada recreated this architecture as a melancholic sign of identity, emphasizing precision of form, local color/lighting, and emptiness. He created a kind of sharp focused nostalgia to express his version of the imagined “la Cuba de ayer,” or yesterday’s Cuba. In this painting, some of the elements of this type of architecture appear broken (column, lack of roof), some are out of place (a stained-glass window on a table), and others seem arbitrary (the modern red and grey wall). The view is not a simple nostalgic gesture as in the earlier work. As the title indicates, it is a still life, meaning a dead subject (Naturaleza muerta), placed in a theatrical stage (Barragan’s Scenography). Luis Ramiro Barragan, was an influential Mexican architect, whose interiors often have the look of a performance space. In this painting, Calzada offers a self-conscious melancholic fantasy in full color.

Arturo Rodríguez is an expressionist painter and draftsman, who likes to work in series, often enthused by literary or artistic works. He emerged as an artist in the late 1970s. His large painting, En el suelo del cielo III (On the Floor of the Sky III), was inspired by a poem of the same name by the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa. The short poem refers to sleeping and dreaming, subjects close to Rodriguez. Against a non-descript background with blue tonalities, which suggest the sky of the title, there is a large arm and tumbling down ladders with falling figures. The entire surface is painted with vigorous brushwork in tune with the depicted fall. The fall, distortions, and strong sense of dislocation offer not a reassuring view of humanity, yet sympathetic. Notice the face of the figures. The image has the quality of a nightmare.

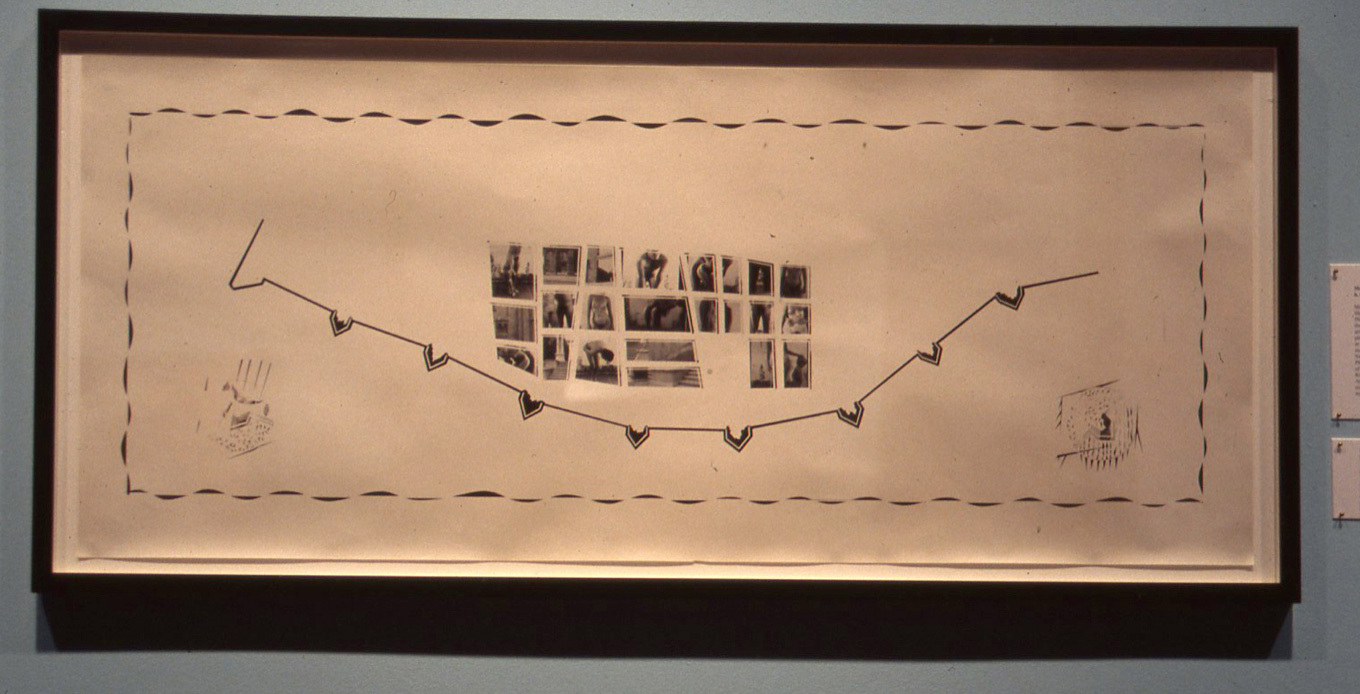

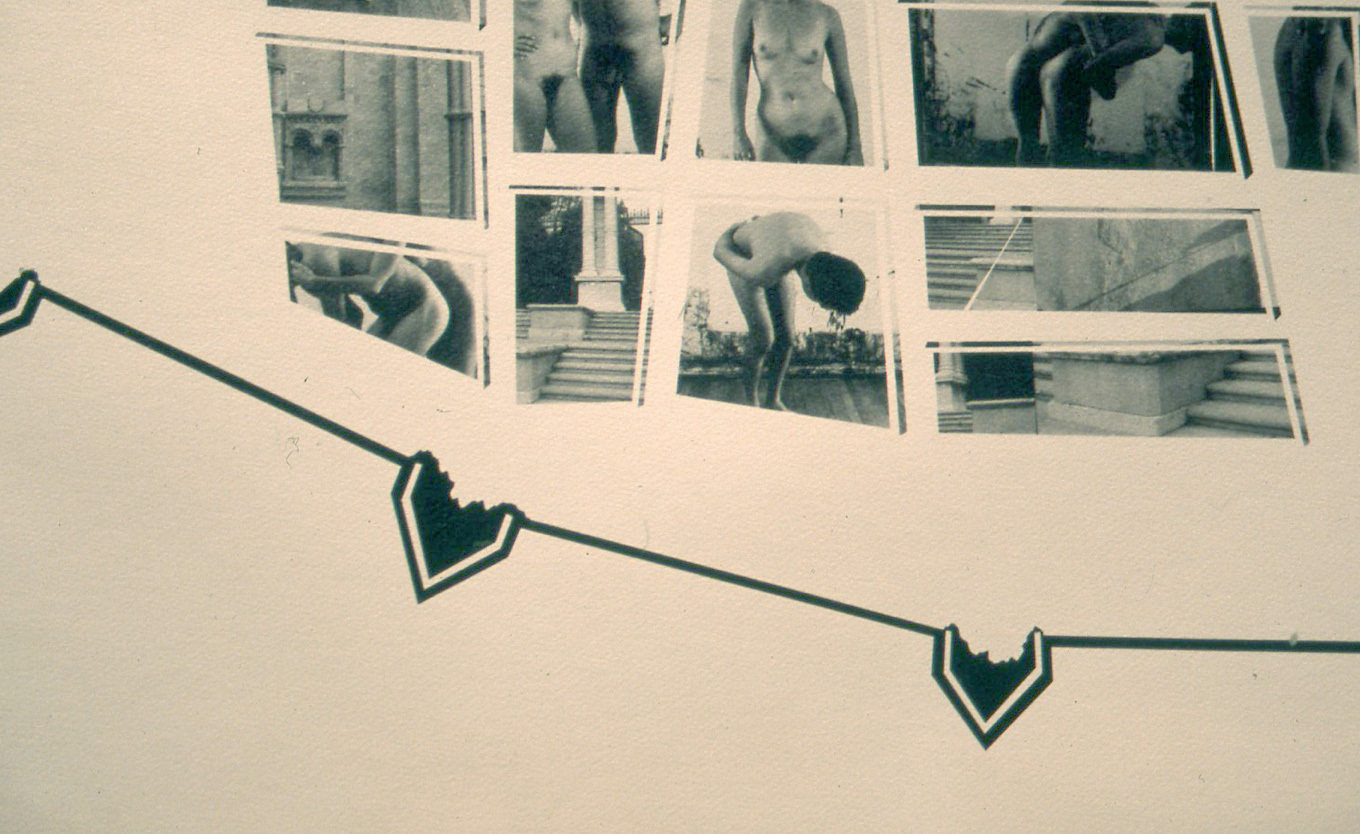

In the case of Maria Martínez-Cañas, the Lowe has an early piece from when she emerged as an artist in the late 1980s. It is a gelatin silver print titled, Amor de ciudad grande II (Big City Love II). At the time, she was pushing the limits of photography. It is both abstract and figurative, drawing and photograph. Inside a margin of thin semi circular forms, there is an elegant curving black line with regularly spaced triangle like forms pointing downwards. It suggests the ground plan of a medieval town’s protective wall. Above it, in the middle of the composition, there is a horizontal grey rectangle made up of more or less rectangular, small, B-grade photographs. Upon closer look, these grey images show a few architectural views and the rest are of female and male nudes in casual poses. Is the line with the triangles protecting the vulnerable nude bodies? In this piece, the viewer moves from being the spectator of a refined abstract design to being a voyeur.

As you would expect, seeing one artwork by an artist barely gives an idea of their art and only at one point in time. The takeaway is that each represents a piece of the puzzle that is an artist’s production. In the case of Cano, here is one of his outstanding rod puppets. In that of Trasobares, it offers one of his most complex installations, especially those with a Cuban theme. Falero’s painting is unique within his production in regards to content. Bencomo is even more unique within his oeuvre in regards to form. Brito’s mixed media piece is one of her more poetic boxes. Rodríguez’ painting offers a textbook example of his unique figurative style, syncopated compositions, and dexterity with the brush. Calzada’s work openly exposes, more than most of his other paintings, the theatre of his melancholia. And in the case of Martínez-Canas, the collection offers a fine lyrical example of her early work. Anyone studying the art of Cuban Americans or that of any of these individuals would do well to look at these first rate works, which to boot are available in a museum. Exhibitions of the Cuban and Cuban American art collection at the Lowe Art Museum would make its fine holdings better known and appreciated in this community. In the best of cases, it would further investigation in this growing area of art history study.

In the mid 1990s, the defunct Cuban Museum of Art and Culture became the Cuban Museum of the Americas. Yes, a strange name. It’s last director, Ileana Fuentes, asked a good number of artists of the Miami Generation, those associated with the Mariel Boatlift of 1980, and artists of Havana’s 1980s Generation then living in Miami, to donate one of their artworks to the museum. Most of the artists heeded the call and gifted good to excellent pieces. She then held a rare and beautiful exhibition of these three groups of artists, which to the best of my knowledge, had never been seen together. Unfortunately, it did not have a catalogue, which today could testify to the vibrant scene of art done by Cubans and Cuban Americans in Miami of the 1980s and 1990s. By Cuban Americans, I mean those artists formed in the United States. The contribution of these discrete groups of artists to the Miami art world has hardly being documented and never assessed. When the Cuban museum folded a few years later, it’s entire collection was given to the Lowe Art Museum. At the same time, it’s archives passed to the Cuban Heritage Collection of the Richter Library at the University of Miami, which makes the Lowe a natural repository for the art.

In 1999, soon after the Lowe Art Museum acquired the collection, it’s then director Brian Dursum asked me to curate a show based on those holdings. The result was an exhibition entitled From Modern to Contemporary Cuban Art (2000). It had to be curated in a hurry to showcase the museum’s new acquisition and it was done without a budget, thus no catalogue.

The show included a fraction of the collection given to the Lowe, and drew from four outstanding multi-works donations given to the Cuban Museum during its brief existence. I like to think of them as collections within the collection. There are the works secured by Iliana Fuentes, mentioned above. The collection of Wifredo Lam’s drawings and rare portrait paintings donated by the Cuban ethnographer Lydia Cabrera. She was a close friend of the artist in the 1940s. An aside, there are enough works on paper by Lam in the Lowe’s entire collection to curate a comprehensive retrospective exhibition of this artist. Then, there is the small, but historically significant collection given by the Nicaraguan journalist Eduardo Aviles Ramirez. While living in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, Aviles Ramirez befriended and helped many visiting Cuban artists, gathering an intimate collection of modern Cuban art at its inception. A much larger donation is the former collection of Rafael Casalins, the food critic for El Nuevo Herald in the 1980s. This is a wide ranging collection of Cuban modern and contemporary art, including eight 1950s paintings by the group Los Once, rare in Miami until the recent interest in Cuban abstract art. To be sure, the Lowe Art Museum’s collection of Cuban and Cuban American art is more extensive than the holding sources mentioned above. It is the largest in any museum in Dade County.

I have a modest proposal for the Lowe: dedicate one sizable room for a month or six weeks every year to showcase different parts of the Cuban and Cuban American art collection. I will begin with an imaginary show of what I consider salient pieces by the Miami Generation. This name is given to a generation of Cuban American artists, who came to Miami as adolescents, grew up in this city, and have been working here as artists for the last forty years. It is a very loose group of artists, some have MFA degrees, others a BA or AA, and a few are self-taught. For more information about many of these artists, please see the catalogue: The Miami Generation Revisited, The Art Museum, Ft. Lauderdale, 2013 (Please see one of the articles in that catalog in this website.)

My imaginary exhibition, besides my personal taste, aims to suggest the variety of themes, media, and quality (that problematic, but I believe still subjectively valid word) of works produced by the artists of that generation. Giving my primary interest in making the works visible, I make no attempt to come up with an overarching theme or theory regarding the art of Cuban Americans. I will leave that for another time, or even better, another curator. My curatorial choice includes: Maria Brito’s The Room Upstairs: Self-Portrait with Two Friends 1984; Mario Bencomo’s Requiem, 1993; Pablo Cano’s Princess Havana 1999; Humberto Calzada’s Still Life in Barragan’s Scenography 1987; Emilio Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope 1993; Maria Martínez Cañas’ Big City Love II, 1986-1987; Arturo Rodríguez’s On the Floor of the Sky III, 1994; and Cesar Trasobares’s E-Nino, 1996-2000.

On entering the space you would be greeted by Cano’s Princess Havana. Cano is a mixed media sculptor, painter, and puppeteer, who emerged as an artist around 1980. The humorous assemblage in question is a rod puppet, which depicts a royal lady, made of the most unlikely materials. She stands in front of a microphone and has the floor. The piece can be seen as a symbol of Havana, given its emblematic quality. It can also be interpreted as a light melancholic representation of the Cuban high class who went into exile. I will bypass the most obvious reading of her being an entertainer, given the microphone. (For a full discussion of this piece, please see Cano’s Royal Ladies).

On the opposite end of the room, I would place Cesar Trasobares’ installation E-Nino. Trasobares is a conceptual artist and activist, who emerged as an artist in the late 1970s. E Nino is a map of the island of Cuba painted on the wall, with works on paper place around it. Originally, when shown at the Cuban museum, it had a different title, which alluded to the exhibition and was event specific: A Gift with Cuban Motif. At the Lowe, the map was painted grey and the names of the Cuban cities and towns were substituted with the name of foreign cities. This displacement of names aptly suggest the Cuban exodus, it’s goings and comings. Geography becomes relative and borders expand. The works on paper above and below the map are mostly personal and relate to periods in his long trajectory. Some relate to his interest in furniture, others to his investigation of the Quinceñera coming of age parties, a couple are of childhood photos with superimposed writings, and a few are grocery advertisements. These last ones reveal Trasobares as an artist-anthropologist of Miami Cuban popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s. One of the early successful business ventures of Cuban exiles in Miami was owning neighborhood grocery stores. Here Cubans could buy the products used in their cuisine, a lifeline to keeping tradition alive and their stomach satisfied. Once or twice a week, the store owner printed on 8 x 10 white paper the specials of the week, and delivered the ads to neighborhood homes, placing them in the mailbox or the door. Trasobares appropriated these crude advertisements and placed them in art exhibitions, not for their aesthetic design, but for their mundane yet significant social/cultural value. This entire installation does not speak about yesterday Cuba, but about what it’s exiles and immigrants took with them to their new place: a strong sense of identity, nostalgic memories, and in lots of cases, the know how to forge ahead.

On the walls between the two mentioned artworks, I would place the two-dimensional and relief pieces. Mario Bencomo is an abstract painter, who mostly works on canvas and large

paper format. He emerged as an artist in the early 1980s. One of my favorite pieces by him is in the Lowe collection, titled Requiem. This is a small mixed media on wood, which rich surface is painted in purple with a loose triangular area of vibrant red at the center. This center is accentuated by a three-dimensional ring, the one defined shape in the composition. Bencomo often works in series and this one belongs to the Torquemada Series. Tomás de Torquemada was a Castilian Dominican friar, and the first Grand Inquisitor in Spain's movement to homogenize religious practices with those of the Catholic Church. He lived in the late 15th century. Bencomo’s painting is a requiem for all of the victims of that phase of the Spanish Inquisition. It is a meditative image with a strong, somber mood. It’s emotional impact is much greater than its size.

Next, I would place another painting, which also obliquely references the Catholic mass. Emilio Falero’s As We Wait in Joyful Hope is painted in his tight realistic style, yet differs in subject matter from most of his work. Falero is a figurative painter, who emerged as an artist in the mid-1970s, and was influenced by the New Realism movement of that time. The Lowe Art Museum’s anonymous quote in its website offers an excellent introduction to this painting. “(It) is an allegory of world domination and the historical transience of political power. A lush Cuban landscape stretches eternally beyond a crumbling column encroached upon by a vine and flower, on top of which sits Napoleon’s tri-corner hat and boots. The artist implies that nature, enduring, will never succumb to man, no matter how enormous and mighty the human aggression, nor can corruption survive. While Napoleon was never a part of the political history of Cuba, for Falero, he symbolizes and represents the inevitable end of oppression and oppressor. Given Cuba’s recent political history, the painting also operates on another more literal level of interpretation, expressed through the title, which comes from a prayer said during Catholic mass.”

Maria Brito is a mixed media sculptor, painter, and professor, who emerged as an artist around 1980. Next, I would hang Brito’s personal and poetic The Room Upstairs: Self-Portrait with Two Friends. This intimate assemblage is a shallow box. It’s lower part represents an empty interior with tile floor, blue walls, and a white closed door in the center; the upper part of the composition, a second floor, depicts three similar looking girls dressed in white. The one to the left has a fully colored butterfly next to her shoulder and the center figure is divided down the middle of her body. The first floor suggests quietness and solitude, the second floor, fantasy and freedom. The similarity of the girls and the splitting of one of the girl’s body make me think of imaginary friends, while the butterfly conjures thoughts of liberty and transformation. This mesmerizing piece has the quality of a dream or a memory. Brito dove deep into her past to better know herself, and in the end, give us all an insight into childhood and recollection.

I would continue with the theme of memory, if of a different nature and means of expressing it: Humberto Calzada’s Still Life in Barragan’s Scenography. Calzada is a realist painter and printmaker, who emerged as an artist in the mid 1970s. This painting is from the second phase of his long exploration of Cuban Colonial architecture as a symbol of homestead. Craftsmen from southern Spain and their Cuban born descendants created a more or less unique architecture in the19th century for the island’s white elite. In the 1940s, when this architecture was deteriorating, a generation of architects, artists, and intellectuals foregrounded it as a sign of that which is Cuban, especially in relation to its Spanish heritage, which they argued was the dominant side of the Cuban identity. In exile, Calzada recreated this architecture as a melancholic sign of identity, emphasizing precision of form, local color/lighting, and emptiness. He created a kind of sharp focused nostalgia to express his version of the imagined “la Cuba de ayer,” or yesterday’s Cuba. In this painting, some of the elements of this type of architecture appear broken (column, lack of roof), some are out of place (a stained-glass window on a table), and others seem arbitrary (the modern red and grey wall). The view is not a simple nostalgic gesture as in the earlier work. As the title indicates, it is a still life, meaning a dead subject (Naturaleza muerta), placed in a theatrical stage (Barragan’s Scenography). Luis Ramiro Barragan, was an influential Mexican architect, whose interiors often have the look of a performance space. In this painting, Calzada offers a self-conscious melancholic fantasy in full color.

Arturo Rodríguez is an expressionist painter and draftsman, who likes to work in series, often enthused by literary or artistic works. He emerged as an artist in the late 1970s. His large painting, En el suelo del cielo III (On the Floor of the Sky III), was inspired by a poem of the same name by the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa. The short poem refers to sleeping and dreaming, subjects close to Rodriguez. Against a non-descript background with blue tonalities, which suggest the sky of the title, there is a large arm and tumbling down ladders with falling figures. The entire surface is painted with vigorous brushwork in tune with the depicted fall. The fall, distortions, and strong sense of dislocation offer not a reassuring view of humanity, yet sympathetic. Notice the face of the figures. The image has the quality of a nightmare.

In the case of Maria Martínez-Cañas, the Lowe has an early piece from when she emerged as an artist in the late 1980s. It is a gelatin silver print titled, Amor de ciudad grande II (Big City Love II). At the time, she was pushing the limits of photography. It is both abstract and figurative, drawing and photograph. Inside a margin of thin semi circular forms, there is an elegant curving black line with regularly spaced triangle like forms pointing downwards. It suggests the ground plan of a medieval town’s protective wall. Above it, in the middle of the composition, there is a horizontal grey rectangle made up of more or less rectangular, small, B-grade photographs. Upon closer look, these grey images show a few architectural views and the rest are of female and male nudes in casual poses. Is the line with the triangles protecting the vulnerable nude bodies? In this piece, the viewer moves from being the spectator of a refined abstract design to being a voyeur.

As you would expect, seeing one artwork by an artist barely gives an idea of their art and only at one point in time. The takeaway is that each represents a piece of the puzzle that is an artist’s production. In the case of Cano, here is one of his outstanding rod puppets. In that of Trasobares, it offers one of his most complex installations, especially those with a Cuban theme. Falero’s painting is unique within his production in regards to content. Bencomo is even more unique within his oeuvre in regards to form. Brito’s mixed media piece is one of her more poetic boxes. Rodríguez’ painting offers a textbook example of his unique figurative style, syncopated compositions, and dexterity with the brush. Calzada’s work openly exposes, more than most of his other paintings, the theatre of his melancholia. And in the case of Martínez-Canas, the collection offers a fine lyrical example of her early work. Anyone studying the art of Cuban Americans or that of any of these individuals would do well to look at these first rate works, which to boot are available in a museum. Exhibitions of the Cuban and Cuban American art collection at the Lowe Art Museum would make its fine holdings better known and appreciated in this community. In the best of cases, it would further investigation in this growing area of art history study.

From Modern to Contemporary Cuban Art

2000

Pablo Cano

Cesar Trasobares

Mario Bencomo

Emilio Falero

Maria Brito

Humberto Calzada

Arturo Rodríguez

Arturo Rodríguez, detail

Maria Martínez-Cañas

Maria Martínez-Cañas, detail