Juan A Martinez, 2017

I first met Fernando García (1945-1989) in his small apartment in Coral Way while I was doing interviews for a lecture on The Miami Generation exhibition at the Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture. It was the summer of 1983. He was medium height, thin, quick with a smile, and was an easy conversationalist. He told me that he arrived from Cuba as part of the Operation Pedro Pan, which between 1960 and 1962 brought over 14,000 unaccompanied children to Miami. The operation was fueled by parents fearful of their children’s indoctrination by the Marist-Leninist turning of the Cuban government and was carried out in secrecy by the Catholic Welfare Bureau. In Miami, he studied at Belén Jesuit school. Like the majority of the historical Cuban exile, he was white and Catholic. García then went on to receive a B.S. in Physics and Mathematics from the University of Georgia in Athens (1968). Later he earned graduate credits in mathematics from Georgia State University, where he also pursued a masters degree in fine arts (1968-69). At the same time, he exhibited his first works at the Heath Galleries in Atlanta. After a stint in the army and work in Atlanta, he went to New York City and in the mid 1970s returned to Miami.

Miami around 1980 was the site of new artistic energy. The Miami-Dade County Public Library system and the art galleries of Miami Dade Community College offered alternative spaces, commercial art galleries increased in numbers, the new county sponsored Miami Art Center opened in downtown, and the Dade-County Art in Public Places program grew in leaps and bound. A very loose group of young Cuban American artists emerged at that time, García being one of them, and contributed to the budding art scene. Fernando worked in a variety of media, he did drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations and performances. Most of the work has a strong conceptual base, a minimal precise geometry, and intense hues. A lot of his art was influenced by his background in science and in particular mathematics. The work ranged from the very personal (his many Calendar pieces 1970s-80s), to exploration of natural phenomena (the Daylight series, 1978), to celebratory (Holiday Spheres, 1983 commissioned by the Center for the Fine Arts for its inauguration), to socio-political commentary (Anti-Bilingual Bigot, 1987), and more. He kept a high profile in the Miami art scene of the 1980s. Fernando García died of the AIDS virus at the end of that decade.

This essay is a rumination on my two favorite pieces of Garcia’s work: 10,865, 1980 and A Martí 1983. The two were meant as one-time installations, but luckily have survived. I am fortunate to have seen them when they were first shown and again a couple of years ago. The second time around I liked them even better.

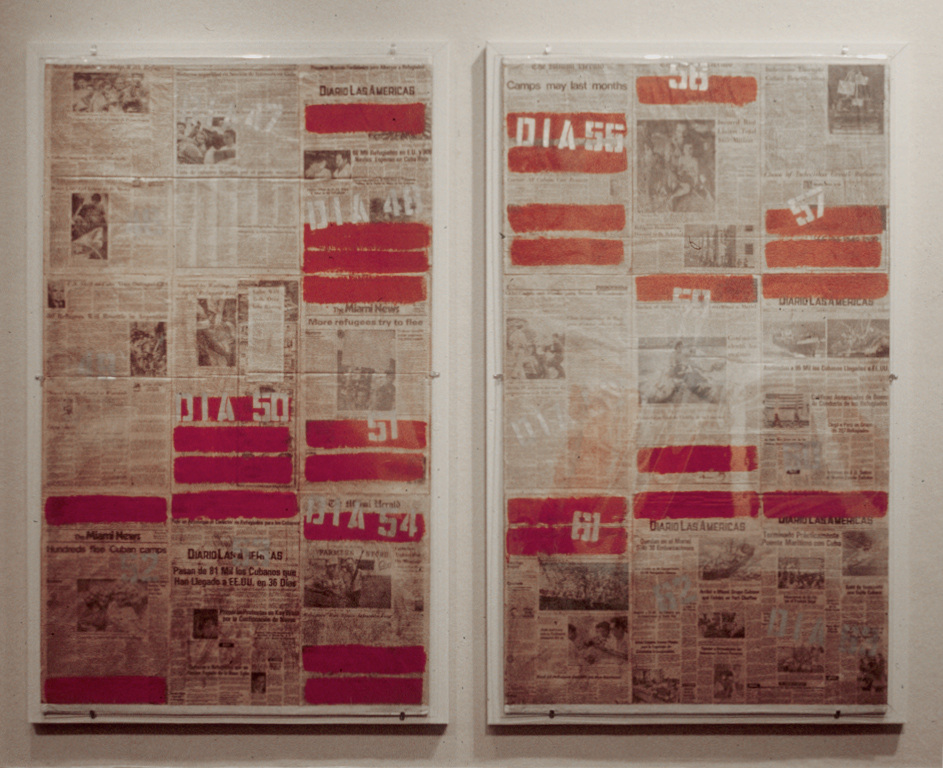

10,865 was first shown in the Miami-Dade County Public Library’s Main Branch in downtown. It was included in an exhibition of the same title about the Mariel Boatlift of that year. The exhibition took place as the boatlift unfolded and the number of the title refers to the number of Cubans who took refuge in the Peruvian embassy in Havana leading to the mass emigration in question. Between April 15th and October 31st of 1980 around 150,000 Cubans left Mariel harbor and arrived in Key West. His piece consists of seven collages measuring about 6 x 4 feet each and made of the pages of local newspapers covering the event. Each collage chronicles various days. He used red paint to block the parts unrelated to the story and used an stencil to mark the days: DIA 1, DIA 2, etc.

From a distance, the precise letters and columns, larger stenciled letters/numbers, and red bars give the pieces a minimal look. The color red, however, signals the emotional content once viewed up close. The daily events told in words and photos are highly dramatic: overcrowded boats, drownings, disoriented people with nothing but their raggedy clothes, and the mentally ill and criminals forced into the boats by the Cuban government. García held up a magnifying glass to the situation. He reinforced the news and increased awareness. His collages bear witness, like few other art on the subject, to a major event in the long relations between the US and Cuba, not to mention the history of Miami. The piece is a contemporary version of what used to be called history painting. The participant of a major historical exodus, Operation Pedro Pan, made a moving work of art with another such event. Fortunately the public library bought 10,865, framed and preserved it. In time the newspaper has gotten a sepia tone giving it a certain patina and the gravitas of an old historic document. When I saw it last at the Main Library auditorium, the overall impression I received was a commanding visual presence, greater than the sum of its parts.

Miami around 1980 was the site of new artistic energy. The Miami-Dade County Public Library system and the art galleries of Miami Dade Community College offered alternative spaces, commercial art galleries increased in numbers, the new county sponsored Miami Art Center opened in downtown, and the Dade-County Art in Public Places program grew in leaps and bound. A very loose group of young Cuban American artists emerged at that time, García being one of them, and contributed to the budding art scene. Fernando worked in a variety of media, he did drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations and performances. Most of the work has a strong conceptual base, a minimal precise geometry, and intense hues. A lot of his art was influenced by his background in science and in particular mathematics. The work ranged from the very personal (his many Calendar pieces 1970s-80s), to exploration of natural phenomena (the Daylight series, 1978), to celebratory (Holiday Spheres, 1983 commissioned by the Center for the Fine Arts for its inauguration), to socio-political commentary (Anti-Bilingual Bigot, 1987), and more. He kept a high profile in the Miami art scene of the 1980s. Fernando García died of the AIDS virus at the end of that decade.

This essay is a rumination on my two favorite pieces of Garcia’s work: 10,865, 1980 and A Martí 1983. The two were meant as one-time installations, but luckily have survived. I am fortunate to have seen them when they were first shown and again a couple of years ago. The second time around I liked them even better.

10,865 was first shown in the Miami-Dade County Public Library’s Main Branch in downtown. It was included in an exhibition of the same title about the Mariel Boatlift of that year. The exhibition took place as the boatlift unfolded and the number of the title refers to the number of Cubans who took refuge in the Peruvian embassy in Havana leading to the mass emigration in question. Between April 15th and October 31st of 1980 around 150,000 Cubans left Mariel harbor and arrived in Key West. His piece consists of seven collages measuring about 6 x 4 feet each and made of the pages of local newspapers covering the event. Each collage chronicles various days. He used red paint to block the parts unrelated to the story and used an stencil to mark the days: DIA 1, DIA 2, etc.

From a distance, the precise letters and columns, larger stenciled letters/numbers, and red bars give the pieces a minimal look. The color red, however, signals the emotional content once viewed up close. The daily events told in words and photos are highly dramatic: overcrowded boats, drownings, disoriented people with nothing but their raggedy clothes, and the mentally ill and criminals forced into the boats by the Cuban government. García held up a magnifying glass to the situation. He reinforced the news and increased awareness. His collages bear witness, like few other art on the subject, to a major event in the long relations between the US and Cuba, not to mention the history of Miami. The piece is a contemporary version of what used to be called history painting. The participant of a major historical exodus, Operation Pedro Pan, made a moving work of art with another such event. Fortunately the public library bought 10,865, framed and preserved it. In time the newspaper has gotten a sepia tone giving it a certain patina and the gravitas of an old historic document. When I saw it last at the Main Library auditorium, the overall impression I received was a commanding visual presence, greater than the sum of its parts.

The other artwork of Fernando García that has attached itself to my memory is A Martí (To Martí). The piece was also meant as an ephemeral installation for the famed 1983 Miami’s Cuban Museum exhibition The Miami Generation. Fortunately it was installed again at the 2013 exhibition The Miami Generation Revisited at the Art Museum in Ft. Lauderdale. This site-specific piece, meaning in this case that it was made for a specific space and a specific event, consists of two parts. On one wall is a medium size mirror, placed at eye level, with the outlines of a Cuban flag engraved on it. On the opposite wall there is a text written backwards in white chalk on a black background. It takes the whole wall and looks like a supersized blackboard. Looking at the engraved mirror from a certain angle, the writing becomes legible. The writing is taken from the classic book of the Cuban writer and patriot hero José Martí: La edad de oro. The essays in it were originally published in a magazine of the same name dated to 1889; it’s title, The Golden Age refers to childhood and the varied essays were meant to educate children or young people. García chose parts of a section titled Musicos, poétas y artistas, in which Martí comments on the Renaissance artists Michelangelo, Raphael and Da Vinci. He seemingly borrowed the idea of writing backwards to be understood by using a mirror from Da Vinci. Of the three artists, I imagine García related most to the latter because of his and Da Vinci’s scientific interests.

Artistically, A Marti is a personal version of Minimalism and Conceptual art, elegant and poetic. The piece also speaks to its cultural site and possibly to the nature of memory, the keystone of exile thinking. Martí’s writings have been overused on both sides of the Florida straits to support contrasting political ideologies. García opted instead for using his seldom quoted art writings, acknowledging other aspects of Martí’s thought and one that befits the site, an art museum. The reflective quality of the piece, looking back both literally and historically, and it’s distortions, offer an intelligent metaphor for the nature of recollections, and in this case, cultural memory. It’s reading takes us into a historical labyrinth. When seen in 2013 at the Ft. Lauderdale museum, you had 21st century viewers looking at the work of a 20th century Cuban American artist, who was working with the writings of a 19th century Cuban poet, who was writing about 16th century artists; all seen through the idea of one of those artists: backward writings and mirror. One more thought. García taught in Atlanta and Miami, he liked to educate and used blackboard motifs in other artworks, like Anti-Bilingual Bigot. Unlike Da Vinci, García writings in A Marti are not in a book, but on what resembles a blackboard, they are not intimate, they are public and like its source, Marti’s book, they mean to teach.

Fernando García gave his bout with AIDS a heroic fight. Towards the end, he lost a lot of his sight, weight, and energy, but continued to move about and work. I remember seeing him hop into a Metrorail car going downtown, I forget for what reason he was going there. He was hardly recognizable, but pushed on. I also remember seeing a large installation done by him when he could barely see. It was made of cut out paper showing people’s silhouettes. It is sad that he and his work have been largely forgotten. Exceptions are the one person show, Fernando García: On the Line-A Retrospective, held at the M-DC Public Library in 2003, The Miami Generation Revisited exhibition in the Art Museum of Ft. Lauderdale in 2013, and his permanent neon light sculpture Making Purple,1986, at the Okeechobee Metro Rail station. One person who has kept the torch alive is his ever-faithful friend Nan Clark. Luckily a good amount of his work and documentation of it has survived. When will one of Miami’s art museums organize a much-deserved retrospective exhibition about a local artist who made a valuable contribution to the emergent art scene in this city in the 1980s?

Artistically, A Marti is a personal version of Minimalism and Conceptual art, elegant and poetic. The piece also speaks to its cultural site and possibly to the nature of memory, the keystone of exile thinking. Martí’s writings have been overused on both sides of the Florida straits to support contrasting political ideologies. García opted instead for using his seldom quoted art writings, acknowledging other aspects of Martí’s thought and one that befits the site, an art museum. The reflective quality of the piece, looking back both literally and historically, and it’s distortions, offer an intelligent metaphor for the nature of recollections, and in this case, cultural memory. It’s reading takes us into a historical labyrinth. When seen in 2013 at the Ft. Lauderdale museum, you had 21st century viewers looking at the work of a 20th century Cuban American artist, who was working with the writings of a 19th century Cuban poet, who was writing about 16th century artists; all seen through the idea of one of those artists: backward writings and mirror. One more thought. García taught in Atlanta and Miami, he liked to educate and used blackboard motifs in other artworks, like Anti-Bilingual Bigot. Unlike Da Vinci, García writings in A Marti are not in a book, but on what resembles a blackboard, they are not intimate, they are public and like its source, Marti’s book, they mean to teach.

Fernando García gave his bout with AIDS a heroic fight. Towards the end, he lost a lot of his sight, weight, and energy, but continued to move about and work. I remember seeing him hop into a Metrorail car going downtown, I forget for what reason he was going there. He was hardly recognizable, but pushed on. I also remember seeing a large installation done by him when he could barely see. It was made of cut out paper showing people’s silhouettes. It is sad that he and his work have been largely forgotten. Exceptions are the one person show, Fernando García: On the Line-A Retrospective, held at the M-DC Public Library in 2003, The Miami Generation Revisited exhibition in the Art Museum of Ft. Lauderdale in 2013, and his permanent neon light sculpture Making Purple,1986, at the Okeechobee Metro Rail station. One person who has kept the torch alive is his ever-faithful friend Nan Clark. Luckily a good amount of his work and documentation of it has survived. When will one of Miami’s art museums organize a much-deserved retrospective exhibition about a local artist who made a valuable contribution to the emergent art scene in this city in the 1980s?